Contact

Contact

Aboriginal Sites

Aboriginal people have lived in Australia for more than 40,000 years. There’s evidence of this everywhere, in rock art, stone artefacts and other sites across the country. But if you thought Aboriginal heritage was just about rock art, think again. Aboriginal culture is much bigger than this, and it’s a living, ongoing thing. It is deeply linked to the entire environment – plants, animals and landscapes. The land and waterways are associated with dreaming stories and cultural learning that is still passed on today. It is this cultural learning that links Aboriginal people with who they are and where they belong.

Many areas of Australia have cultural significance to Aboriginal people. They reflect the ways in which Aboriginal people view their cultural heritage. These places carry a relationship between one person and another, and between people and their environment.

Rock Art

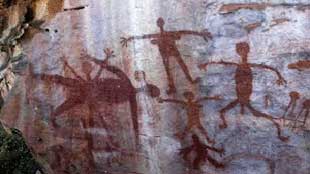

Australia has more rock art sites than any other country with at least 100,000 and perhaps as many as 125,000. Rock art is the common denominator in most Aboriginal sites – where there was no rock, tree carving was practised. This art takes the form of paintings on rock surfaces and illustrations carved into rock surfaces. Most paintings occur in rock overhangs and caves, whereas engravings are most commonly found on the top of ridges of headlands, at water level around the bays and coves of the harbour or near a waterhole or campsite, they are generally horizontal rather than vertical. Every piece of art had a particular significance to the tribe, some told of their tribal ancestry, others identified the land as theirs. No art was created without a reason, therefore all art that remains today had tribal significance, though often that significance is no longer known following the destruction of the culture and breaking of the continuity of tribal religious and cultural activity.

The creation and maintenance of existing of rock art was the responsibility of select tribal members and no other person was permitted to become involved in rock artistry. Under tribal law, the rock art which survives today can only be re-grooved or repainted by authorised tribal members. As many of the original tribes and clans were wiped out and have no survivors, their art cannot be touched by other tribe and clan members, which is why much of the rock art around Australia is not being maintained.

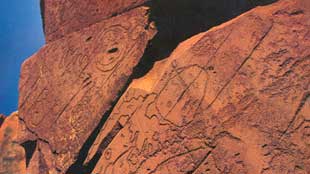

Engravings are often shallow grooves less than 5 mm deep formed through the pecking of a series of holes in the soft sandstone by a hard rock (often brought in from another area). These holes were then joined by scraping away the rock between them, possibly over time and repeatedly, at ceremonies. As few sites are maintained, weathering by wind and water erosion, cracking and flaking of the rock surface, people walking over them and pollution has caused irreparable damage. Much of the art has been weathered away completely, and only those sites that are protected from the elements and man, or are in areas where the rock is hard and resists erosion, have survived. As they are best seen in low light, early morning or late evenings are the best viewing times. Viewing at night by torch light, with a diverse rather than concentrated beam, is also recommended though this limits photography.

Rock engraving is most common near the coast, whereas inland, painting is more prolific. The only colours used in painting were white, black and back, with yellow being used sparingly. White came from pipe clay; black from charcoal; red ochre came from nodules of laterite or ironstone; yellow was created from the dust of ants’ nests, which might explain its rarity.

Motifs seen in rock art vary from animals (often recognisable only after you have disentangled the lines), hands, footprints (human footprints are known as mundoes, pronounced mun-doe-ees), small stick figures of humans and larger, more impressive figures of ancestors. Animals include fish, eels (the most common), kangaroos, emus, koalas, goannas, echidnas and dolphins.

Some of the most beautiful Australian Aboriginal art using a naturalistic art style is found in the rock art across northern Australia, the best- known regions being the Kimberley and Kakadu regions. One form of this style is where the internal anatomy of an animal is also shown in the painting, and hence this is called X-ray art. This feature appears occasionally in the very old art of both the Kakadu and Kimberley regions, but really took off in the art of the Kakadu region over the past thousand years or so. This X-ray style continues today with the commercial art produced on barks and paper for the tourist market by Aboriginal people from that region.

Iconic Rock art Sites of Australia

Economic Sites

Axe grinding grooves and water hole

Economic Sites is the term used to describe campsites which show evidence of occupation. Often close to or within rock overhangs and caves used to give shelter, evidences of occupation include middens (piles of discarded shells at feasting sites), fish traps, scarred trees (where the bark of red river gums have been removed to form shields, material for rope making or medicines or carved to identify a burial site), cooking mounds, wells, watering holes (often depressions carved into flat rock surfaces used to catch the water), remnants of discarded tools, quarries and axe sharpening grooves.

Tools and implements reflect the geographical location of different Aboriginal groups. For example, coastal tribes used fishbone to tip their weapons, whereas desert tribes used stone tips. While tools varied by group and location, Aboriginal people all had knives, scrapers, axe-heads, spears, various vessels for eating and drinking, and digging sticks.

Aboriginal people achieved two world firsts with stone technology. They were the first to introduce ground edges on cutting tools and to grind seed. They used stone tools for many things including: to make other tools, to get and prepare food, to chop wood, and to prepare animal skins.

After European discovery and English colonisation, Aboriginal people quickly realised the advantages of incorporating metal, glass and ceramics. They were easier to work with, gave a very sharp edge, and needed less resharpening. Their traditional tools and implements are no longer used but many of the sites where they were created – axe sharpening grooves by creeks and rivers and trees where the bark has been removed to create a bark canoe, for example, still remain.

Middens

Middens are the rubbish dumps at eating sites which, over thousands of years, take on the appearance of small hills rather than a pile of refuse. Archaeological research has found that Berry Island on Sydney’s lower north shore is one gigantic midden, and might have been nothing more than a sand bar surrounding a rocky outcrop had the Aborigines not chosen it as a favourite camping site. Most middens on the water’s edge are comprised of discarded shells of edible species such as oysters, whelks, clams, cockles and mussels. Being an essential part of any camp or feeding site, they can also contain stone implements, bones of fish, birds and marsupials and plant remains. The latter are rarely detectable by the human eye, and after they have rotted away give the appearance of a mound of earth. Middens are most common outside rock shelters on beaches, headlands, river banks and the tops of ridges and hills. Middens in open areas are the hardest to find as they are often covered with grass or vegetation or have been bulldozed. Rubble at a site can tell the size of the gatherings, what time of the year it was used by identifying the types of food eaten, and how many seasons the midden was used. The latter is determined by the number of layers.

Meeting Places

The Aboriginal people had specific places where different group met to trade and partake on Corroborrees together. Meeting places were often marked by stone arrangements. Farm Cove near the Sydney Opera House was such a place. Judge Advocate David Collins recorded details of the early colionials’ first encounters with Aboriginal culture to which they had been invited to experience – a corroboree and initiation ceremony in February 1795. Collins recorded a space had for some days been prepared by clearing it of grass, stumps etc., it was an oval figure, the dimensions of it 27 feet by 18, and it was named Yoo-lahang. The ceremony lasted two days, 15 boys from the eastern harbour clans were initiated as warriors by having their front teeth knocked out by the Cammeraigal tribal elders from the North Shore. Farm Cove was also where ritual punishments were meted out against transgressors of tribal law. It was here that Bennelong and Colbey, two of just a handful of Aborigines who developed close ties with the colony, fought a duel in July 1805. Bennelong was badly injured in the fight and eventually died from injuries received in subsequent conflicts with Colbey.

Sacred Sites

Aboriginal sacred sites are areas or places in the Australian landscape of significant Ameaning within the context of the localised indigenous belief system, known as The Dreaming, which has its origins in Dreamtime. Sites sacred to Aboriginal people are part of Australia’s cultural heritage, connecting the land with the cultural values, spiritual beliefs and kin-based relationships of the local people. Hills, rocks, waterholes, trees, plains and other natural features may be sacred sites. In coastal and sea areas, sacred sites may include features which lie both above and below water. Sometimes sacred sites are obvious, such as ochre deposits, rock art galleries, or spectacular natural features. In other instances sacred sites may be unremarkable to an outside observer. They can range in size from a single stone or plant, to an entire mountain range.

The traditional custodians of the sacred sites in an area are the tribal elders. Sacred sites give meaning to the natural landscape. They anchor values and kin-based relationships in the land. Custodians of sacred sites are concerned for the safety of all people, and the protection of sacred sites is integral to ensuring the well-being of the country and the wider community. These sites are or were used for many sacred traditions and customs. Sites used for male activities, such as initiation ceremonies, may be forbidden to women; sites used for female activities, such as giving birth, may be forbidden to men.

In some areas such as Sydney, NSW, sacred sites were located on hilltops which offered panoramic views of the tribal lands. High ground was were preferred as it gave a commanding view of each clan’s territory – the sites often marked the border between territories. The women were not permitted at such sites and the chance of them coming across them by accident was lessened if they were located away from the tribal hunting grounds. A pre-requisite for such sites was a large slab of flat rock upon which engravings recording tribal history and culture could be made.

All state and territory governments have enacted legislation relating to the protection and management of sacred sites in Australia. Criminal offences apply under Commonwealth and state and territory laws for unauthorised access to sacred sites. Damage to these sites can also result in civil penalties.

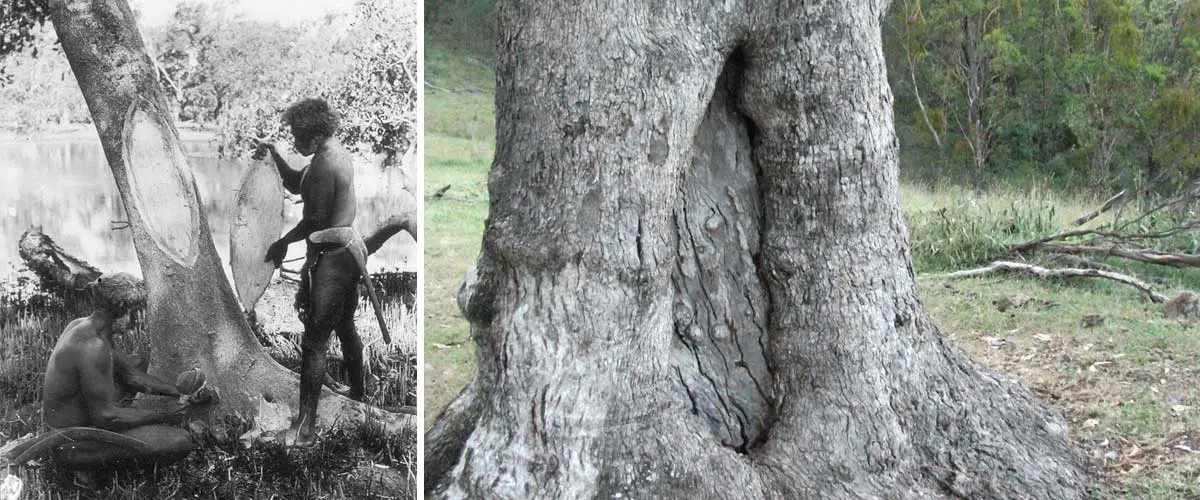

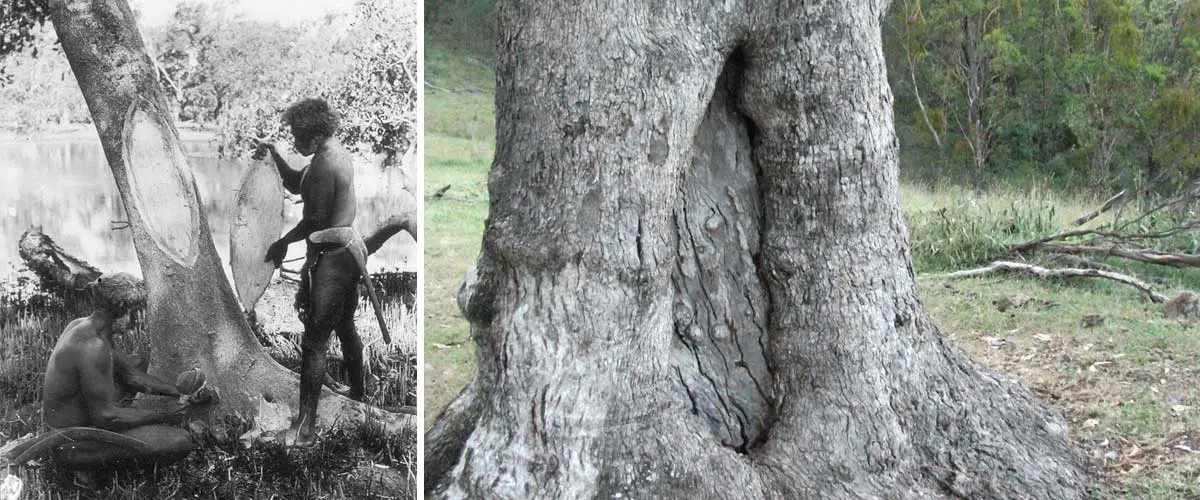

Scarred Trees

As well as a possible food source to the Aborigines of pre-colonial days, trees were an important source of bark from which canoes and shields were made. For an Aboriginal hunter, finding the right tree for a canoe was one thing, getting the bark off and moulding it into a suitable river craft was quite another. In order to reach the desired piece of bark, the craftsman would often need to climb and if there were no low branches, foot holds had to be cut with wooden chisels or stone axes. They prised the bark from the tree with wooden wedges and eased it to the ground with vines used as ropes. This job sometimes involved as many as eight men.

Once prised from the tree with a stone axe, the bark slab would then be fired on a bed of coals so it could be shsped. Wooden struts stopped the bark from curling too much. When dry, the canoe was waterproofed with grease or clay and was ready to launch.

A bark canoe from Avoca Station holds pride of place in the Australian Aboriginal Cultures Gallery in the South Australian Museum. This canoe from Avoca Station on the Darling River is believed to date bake to the 1860’s and is one of the best examples still in existence. A canoe like this was an essential part of life on the River, but often the search for the right tree meant one tribe had to venture into territory which was not theirs by law. The curator of the museum in the early 1930’s, recorded accounts from Aboriginal people where they actually bartered for access to those inland forests. Whipstick mallee was cut down in some of the mallee areas closer to the river and made into shafts and spears they made very good spears and bundles of these were given to traded to people in the hills up towards Mount barker and the Southern Fleurieu Peninsula and that gave the access to these inland forests.

A well known scarred tree in South Australia is located at Warriparinga off South Road at Darlington; across the road in the heart of suburbia is yet another used for the same purpose to make a cooliman. They would have managed it by sitting in the fork of the tree and using a stone implement to extract a piece for use as a cooliman to carry food or small children or even use it as a digging implement.

Not just any tree could be used to create a bark canoe or hunting implement. River red gums were particularly suitable, which is why most known canoe trees are situated alongside riverbanks. In the Sydney region, there is actually an area in the Hawkesbury River region named Canoelands. It is believed the name is derived from the fact that the trees alongside the river here were particularly suited to canoe making and were a major source of canoe bark for the Aborigines of the Sydney and Hawkesbury River regions of NSW. Similarly, the valley of the Woronora River in Sydney’s south was a source of canoe bark for Aborigines in the Botany Bay and Port Hacking areas. Numerous scarred trees can be seen near overhangs and caves alongside the walking trails of Heathcote National Park.

Protecting Aboriginal Sites

All Aboriginal sites in Australia are protected by acts of parliament. It is illegal to disturb, damage, deface or destroy any relic, a relic being defined as any deposit, object or material evidence relating to indigenous and non European habitation (not being handicraft made for sale). By definition, this includes middens, habitation sites, rock carvings, rock paintings, scarred trees, stencils, stone arrangements, stone implements and tools. Aboriginal sites are protected by law because these sites contain irreplaceable examples of the art and culture of the indigenous peoples of a particular region.

The engraving and rock paintings found at these sites are a reminder of a people who once lived there and as such are valuable part of their history and the history of Australia that will be lost forever if it not treated with respect. Please do not deface or add to the art, as it is part of our heritage. All such sites protected by law, and to deface, modify or remove them in part or in whole is a criminal offence. When Aboriginal places are protected, there are benefits for both the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities. An Aboriginal place declaration recognises that places are (or were) of special significance to Aboriginal culture. It gives the land a higher level of protection, to safeguard its significance to Aboriginal people.

Though they have been given legislative protection, there is little known about the best way to manage Aboriginal sites. To western eyes, the ideal would be to turn the maintenance of sites over to the Aboriginal people. This sounds good in theory, however, under Aboriginal law, only select people are permitted to maintain the art at these sites. Where those select people cannot be found, or if there are no survivors from a particular tribe, no one can touch the art created by and for that tribe. Even so, the art is considered sacred to the Aborigines, so there is reluctance among the Aboriginal communities to maintain the art if it is to turned into something to make money from by showing it to tourists.

Consequently, some authorities have adopted a policy of keeping the public in the dark about many Aboriginal sites, such as those in the Sydney region. The thinking behind it seems to be “what the people don’t know about the people can’t damage”. As the damage caused in the past has occurred mainly as a result of ignorance, one would consider education of the public a better way to deal with the problem than maintaining their ignorance.

Many areas of Australia have cultural significance to Aboriginal people. They reflect the ways in which Aboriginal people view their cultural heritage. These places carry a relationship between one person and another, and between people and their environment.

Australia has more rock art sites than any other country with at least 100,000 and perhaps as many as 125,000. Rock art is the common denominator in most Aboriginal sites – where there was no rock, tree carving was practised. This art takes the form of paintings on rock surfaces and illustrations carved into rock surfaces. Most paintings occur in rock overhangs and caves, whereas engravings are most commonly found on the top of ridges of headlands, at water level around the bays and coves of the harbour or near a waterhole or campsite, they are generally horizontal rather than vertical. Every piece of art had a particular significance to the tribe, some told of their tribal ancestry, others identified the land as theirs. No art was created without a reason, therefore all art that remains today had tribal significance, though often that significance is no longer known following the destruction of the culture and breaking of the continuity of tribal religious and cultural activity.

The creation and maintenance of existing of rock art was the responsibility of select tribal members and no other person was permitted to become involved in rock artistry. Under tribal law, the rock art which survives today can only be re-grooved or repainted by authorised tribal members. As many of the original tribes and clans were wiped out and have no survivors, their art cannot be touched by other tribe and clan members, which is why much of the rock art around Australia is not being maintained.

Engravings are often shallow grooves less than 5 mm deep formed through the pecking of a series of holes in the soft sandstone by a hard rock (often brought in from another area). These holes were then joined by scraping away the rock between them, possibly over time and repeatedly, at ceremonies. As few sites are maintained, weathering by wind and water erosion, cracking and flaking of the rock surface, people walking over them and pollution has caused irreparable damage. Much of the art has been weathered away completely, and only those sites that are protected from the elements and man, or are in areas where the rock is hard and resists erosion, have survived. As they are best seen in low light, early morning or late evenings are the best viewing times. Viewing at night by torch light, with a diverse rather than concentrated beam, is also recommended though this limits photography.

Rock engraving is most common near the coast, whereas inland, painting is more prolific. The only colours used in painting were white, black and back, with yellow being used sparingly. White came from pipe clay; black from charcoal; red ochre came from nodules of laterite or ironstone; yellow was created from the dust of ants’ nests, which might explain its rarity.

Motifs seen in rock art vary from animals (often recognisable only after you have disentangled the lines), hands, footprints (human footprints are known as mundoes, pronounced mun-doe-ees), small stick figures of humans and larger, more impressive figures of ancestors. Animals include fish, eels (the most common), kangaroos, emus, koalas, goannas, echidnas and dolphins.

Some of the most beautiful Australian Aboriginal art using a naturalistic art style is found in the rock art across northern Australia, the best- known regions being the Kimberley and Kakadu regions. One form of this style is where the internal anatomy of an animal is also shown in the painting, and hence this is called X-ray art. This feature appears occasionally in the very old art of both the Kakadu and Kimberley regions, but really took off in the art of the Kakadu region over the past thousand years or so. This X-ray style continues today with the commercial art produced on barks and paper for the tourist market by Aboriginal people from that region.

Axe grinding grooves and water hole

Economic Sites is the term used to describe campsites which show evidence of occupation. Often close to or within rock overhangs and caves used to give shelter, evidences of occupation include middens (piles of discarded shells at feasting sites), fish traps, scarred trees (where the bark of red river gums have been removed to form shields, material for rope making or medicines or carved to identify a burial site), cooking mounds, wells, watering holes (often depressions carved into flat rock surfaces used to catch the water), remnants of discarded tools, quarries and axe sharpening grooves.

Tools and implements reflect the geographical location of different Aboriginal groups. For example, coastal tribes used fishbone to tip their weapons, whereas desert tribes used stone tips. While tools varied by group and location, Aboriginal people all had knives, scrapers, axe-heads, spears, various vessels for eating and drinking, and digging sticks.

Aboriginal people achieved two world firsts with stone technology. They were the first to introduce ground edges on cutting tools and to grind seed. They used stone tools for many things including: to make other tools, to get and prepare food, to chop wood, and to prepare animal skins.

After European discovery and English colonisation, Aboriginal people quickly realised the advantages of incorporating metal, glass and ceramics. They were easier to work with, gave a very sharp edge, and needed less resharpening. Their traditional tools and implements are no longer used but many of the sites where they were created – axe sharpening grooves by creeks and rivers and trees where the bark has been removed to create a bark canoe, for example, still remain.

Middens are the rubbish dumps at eating sites which, over thousands of years, take on the appearance of small hills rather than a pile of refuse. Archaeological research has found that Berry Island on Sydney’s lower north shore is one gigantic midden, and might have been nothing more than a sand bar surrounding a rocky outcrop had the Aborigines not chosen it as a favourite camping site. Most middens on the water’s edge are comprised of discarded shells of edible species such as oysters, whelks, clams, cockles and mussels. Being an essential part of any camp or feeding site, they can also contain stone implements, bones of fish, birds and marsupials and plant remains. The latter are rarely detectable by the human eye, and after they have rotted away give the appearance of a mound of earth. Middens are most common outside rock shelters on beaches, headlands, river banks and the tops of ridges and hills. Middens in open areas are the hardest to find as they are often covered with grass or vegetation or have been bulldozed. Rubble at a site can tell the size of the gatherings, what time of the year it was used by identifying the types of food eaten, and how many seasons the midden was used. The latter is determined by the number of layers.

The Aboriginal people had specific places where different group met to trade and partake on Corroborrees together. Meeting places were often marked by stone arrangements. Farm Cove near the Sydney Opera House was such a place. Judge Advocate David Collins recorded details of the early colionials’ first encounters with Aboriginal culture to which they had been invited to experience – a corroboree and initiation ceremony in February 1795. Collins recorded a space had for some days been prepared by clearing it of grass, stumps etc., it was an oval figure, the dimensions of it 27 feet by 18, and it was named Yoo-lahang. The ceremony lasted two days, 15 boys from the eastern harbour clans were initiated as warriors by having their front teeth knocked out by the Cammeraigal tribal elders from the North Shore. Farm Cove was also where ritual punishments were meted out against transgressors of tribal law. It was here that Bennelong and Colbey, two of just a handful of Aborigines who developed close ties with the colony, fought a duel in July 1805. Bennelong was badly injured in the fight and eventually died from injuries received in subsequent conflicts with Colbey.

Aboriginal sacred sites are areas or places in the Australian landscape of significant Ameaning within the context of the localised indigenous belief system, known as The Dreaming, which has its origins in Dreamtime. Sites sacred to Aboriginal people are part of Australia’s cultural heritage, connecting the land with the cultural values, spiritual beliefs and kin-based relationships of the local people. Hills, rocks, waterholes, trees, plains and other natural features may be sacred sites. In coastal and sea areas, sacred sites may include features which lie both above and below water. Sometimes sacred sites are obvious, such as ochre deposits, rock art galleries, or spectacular natural features. In other instances sacred sites may be unremarkable to an outside observer. They can range in size from a single stone or plant, to an entire mountain range.

The traditional custodians of the sacred sites in an area are the tribal elders. Sacred sites give meaning to the natural landscape. They anchor values and kin-based relationships in the land. Custodians of sacred sites are concerned for the safety of all people, and the protection of sacred sites is integral to ensuring the well-being of the country and the wider community. These sites are or were used for many sacred traditions and customs. Sites used for male activities, such as initiation ceremonies, may be forbidden to women; sites used for female activities, such as giving birth, may be forbidden to men.

In some areas such as Sydney, NSW, sacred sites were located on hilltops which offered panoramic views of the tribal lands. High ground was were preferred as it gave a commanding view of each clan’s territory – the sites often marked the border between territories. The women were not permitted at such sites and the chance of them coming across them by accident was lessened if they were located away from the tribal hunting grounds. A pre-requisite for such sites was a large slab of flat rock upon which engravings recording tribal history and culture could be made.

All state and territory governments have enacted legislation relating to the protection and management of sacred sites in Australia. Criminal offences apply under Commonwealth and state and territory laws for unauthorised access to sacred sites. Damage to these sites can also result in civil penalties.

As well as a possible food source to the Aborigines of pre-colonial days, trees were an important source of bark from which canoes and shields were made. For an Aboriginal hunter, finding the right tree for a canoe was one thing, getting the bark off and moulding it into a suitable river craft was quite another. In order to reach the desired piece of bark, the craftsman would often need to climb and if there were no low branches, foot holds had to be cut with wooden chisels or stone axes. They prised the bark from the tree with wooden wedges and eased it to the ground with vines used as ropes. This job sometimes involved as many as eight men.

Once prised from the tree with a stone axe, the bark slab would then be fired on a bed of coals so it could be shsped. Wooden struts stopped the bark from curling too much. When dry, the canoe was waterproofed with grease or clay and was ready to launch.

A bark canoe from Avoca Station holds pride of place in the Australian Aboriginal Cultures Gallery in the South Australian Museum. This canoe from Avoca Station on the Darling River is believed to date bake to the 1860’s and is one of the best examples still in existence. A canoe like this was an essential part of life on the River, but often the search for the right tree meant one tribe had to venture into territory which was not theirs by law. The curator of the museum in the early 1930’s, recorded accounts from Aboriginal people where they actually bartered for access to those inland forests. Whipstick mallee was cut down in some of the mallee areas closer to the river and made into shafts and spears they made very good spears and bundles of these were given to traded to people in the hills up towards Mount barker and the Southern Fleurieu Peninsula and that gave the access to these inland forests.

A well known scarred tree in South Australia is located at Warriparinga off South Road at Darlington; across the road in the heart of suburbia is yet another used for the same purpose to make a cooliman. They would have managed it by sitting in the fork of the tree and using a stone implement to extract a piece for use as a cooliman to carry food or small children or even use it as a digging implement.

Not just any tree could be used to create a bark canoe or hunting implement. River red gums were particularly suitable, which is why most known canoe trees are situated alongside riverbanks. In the Sydney region, there is actually an area in the Hawkesbury River region named Canoelands. It is believed the name is derived from the fact that the trees alongside the river here were particularly suited to canoe making and were a major source of canoe bark for the Aborigines of the Sydney and Hawkesbury River regions of NSW. Similarly, the valley of the Woronora River in Sydney’s south was a source of canoe bark for Aborigines in the Botany Bay and Port Hacking areas. Numerous scarred trees can be seen near overhangs and caves alongside the walking trails of Heathcote National Park.

All Aboriginal sites in Australia are protected by acts of parliament. It is illegal to disturb, damage, deface or destroy any relic, a relic being defined as any deposit, object or material evidence relating to indigenous and non European habitation (not being handicraft made for sale). By definition, this includes middens, habitation sites, rock carvings, rock paintings, scarred trees, stencils, stone arrangements, stone implements and tools. Aboriginal sites are protected by law because these sites contain irreplaceable examples of the art and culture of the indigenous peoples of a particular region.

The engraving and rock paintings found at these sites are a reminder of a people who once lived there and as such are valuable part of their history and the history of Australia that will be lost forever if it not treated with respect. Please do not deface or add to the art, as it is part of our heritage. All such sites protected by law, and to deface, modify or remove them in part or in whole is a criminal offence. When Aboriginal places are protected, there are benefits for both the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities. An Aboriginal place declaration recognises that places are (or were) of special significance to Aboriginal culture. It gives the land a higher level of protection, to safeguard its significance to Aboriginal people.

Though they have been given legislative protection, there is little known about the best way to manage Aboriginal sites. To western eyes, the ideal would be to turn the maintenance of sites over to the Aboriginal people. This sounds good in theory, however, under Aboriginal law, only select people are permitted to maintain the art at these sites. Where those select people cannot be found, or if there are no survivors from a particular tribe, no one can touch the art created by and for that tribe. Even so, the art is considered sacred to the Aborigines, so there is reluctance among the Aboriginal communities to maintain the art if it is to turned into something to make money from by showing it to tourists.

Consequently, some authorities have adopted a policy of keeping the public in the dark about many Aboriginal sites, such as those in the Sydney region. The thinking behind it seems to be “what the people don’t know about the people can’t damage”. As the damage caused in the past has occurred mainly as a result of ignorance, one would consider education of the public a better way to deal with the problem than maintaining their ignorance.