To the Aboriginal people who live in the Central, Northern and East Kimberley region, including Mitchell Plateau and King Edward River areas of Western Australia, the Wandjina has a deep and meaningful relationship with their heritage and their culture. The Wandjina has for many years appeared on bark coolamons which were used for food gathering and for cradles for newborn babes, ceremonial boomerangs and shields and a myriad of symbolic artefacts – the Wandjina is part of the lives of the tribes who have for many many years lived and hunted and survived in the country of the Wandjina rock art.

In Aboriginal culture, the Wandjina is the Rain Spirit of the Wunambul, Wororra and Ngarinyin language people, the controller of the “Seasons”, the bringer of rain which equals water which equals “life”. Then it says that the Earth is hot and that it breathes; the Earth it breathes, it’s a steam blow up, and it gives cloud to give rain. Rain gives fruit, and everything grows, and the trees and the grass to feed other things, kangaroos and birds and everything. With the completion of their earthly tasks, each of the Wandjina turned into a rockface image. There, the Wandjina spirits continue to live.

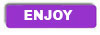

The Wandjina figures are strange, majestic creatures; usually painted against a white background. An oval band encircles the face, except for a break at the chin, and from the outer edge of the head, lines radiate out. They are often shown wearing a headband; eyes and nose form one unit; with lashes encircling both eyes, and they are rarely given a mouth. The body, when there is one, is filled with parallel stripes down the arms and legs. Long lines coming out from the hair are the feathers which Wandjinas wore and the lightning which they control. Wandjina ceremonies to ensure the timely beginning of the monsoon wet season and sufficient rainfall are held during December and January, following which the rains usually begin. The figures are generally drawn surrounded by the totemic beings and creatures associated with them, on which they depend for sustenance, and these caves and rock shelters become a focus of tribal religion and ritual action.

Aboriginal people believe that if the Wandjina are offended then they will take their revenge by calling up lightning to strike the offender dead, or the rain to flood the land and drown the people, or the cyclone with its winds to devastate the country. These are the powers which the Wandjinas can use. Aboriginal culture teaches it is possible for new life to emanate from the figures adorning the cave walls, to re-enter the physical world as unborn children. Such places are sites to which local Aborigines have a deeply spiritual attachment. These Wandjina are seen to have considerable powers and the Aborigines are careful to observe a certain amount of protocol when they approach the paintings, fearing that if they do not, the spirits might take their revenge. This protocol normally consists of calling out to the Wandjinas from several yards’ distance, to tell them a party is approaching and will not harm the paintings. Visitors are required to walked past small fires to be “smoked” before visiting Wandjina sites. This is not only to let the spirits know that “strangers” are visiting, but also so that the Wandjina’s “strong spirit” would not follow visitors home.

Although the paintings represent the bodies of the dead Wandjinas, the Aborigines believe the spirits of the Wandjinas live on in much the same way as they believe the spirits of human beings continue to exist after their death.

The most widely known Aboriginal story from the Kimberly refers to a mythical being. In this legend, Wandjina collaborated to fight against human Aboriginal groups and, in the process, kill many of them. The story is one of cause and effect and is told here in an abridged version. Two children were playing with the bird, Tumbi, who they thought was a honeysucker. However, it was really an owl. They did not see the difference in the eyes and thought the bird was unimportant. The children maimed and blinded the bird. They mocked him by throwing him into the air and telling him to fly, but he could not and fell back to earth.

Tumbi was not just an ordinary bird, he was the owl, the son of a Wandjina. This is why he was able to disappear and go up to Inanunga, the Wandjina in the sky, to complain. The news flew to all the Wandjina who determined to punish the people. A Wandjina named Wodjin called all the Wandjina from throughout the country together, and the owl who had been maimed incited them to revenge. However, they did not know where to find the people, and the lizards and animals which they sent to scout around for them refused to tell where the people were. The animals were sorry for the people, and tried to hide them, knowing that the Wandjina would kill them in revenge for the bad deeds.

But the Wandjina saw the people on a wide flat near the spring at Tunbai. They moved to the top of one of the hills which surround this flat and Wodjin, by stroking his beard, was able to bring heavy rain and floods. The Wandjina divided into two parties and attacked in a pincer movement from the top of the hill. Meanwhile, the Brolgas (birds) had been dancing on the wet ground and had turned it into a bog. The Wandjina drove the people into the boggy water, where they drowned. The people tried to fight back, but they were unable to harm the Wandjina. he boys who had injured the bird were very frightened by the fight, the rain and lightning, and escaped to a large boab tree with a split in it, where they decided to hide. But the tree was really a Wandjina and no sooner were the boys inside than it closed on them and crushed them. The Wandjina, having achieved their aim and revenged the injuries done to the owl, were now able to disperse around the country.

The earliest claim to the discovery of Australia by Europeans was made by a French sailor from Normandy named Jean Binot Paulmier De Gonneville, who claimed that, during a two year voyage of discovery with the intent of finding an ocean route from Europe to the East Indies, he landed on the shores of the Southland early in 1504. In his paper on “Early Voyages to Terra Australis,” printed in 1861, British Admiral Burney, and the eminent English geographer, Mr. Major, told of De Gonneville’s voyage but dismissed his claim, stating instead that the country De Gonneville’s described was the island of Madagascar. This opinion has been generally entertained by navigators and historians ever since, though others have argued he landed in Brazil (Brazilians celebrated the 500th anniversary of his arrival on their shores in 2004 at Carnivale), however there is much evidence to suggest that De Gonneville might well have reached Australia’s shore.

After having rounded the Cape of Good Hope he was assailed by tempestuous weather and driven into calm latitudes. After a tedious spell of calm weather, want of water forced him to make for the first land he could sight. The flight of some birds coming from the south caused him to run a course to the southward, and after a few days’ sail he landed on the coast of a large territory at the mouth of a wide river. There he remained for six months repairing his vessel and making exploratory excursions into the hinterland, establishing contact and maintaining good relations with the inhabitants during his stay. These included a tribe of light skinned people. He left this great Austral Land, to which he gave the name of “Southern Indies,” on 3rd July, 1504, taking with him two of the natives, one of whom was the son of the chief of the people among whom he had resided.

Subsequent discoveries, and a closer scrutiny of the Norman captain’s narrative indicate that De Gonneville’s “Southern Indies” could be the Australian Continent, and that he may well have landed at the mouth of one of the rivers on the north-western coast, namely the Glenelg or Prince Regent Rivers of North-west Australia. De Gonneville’s description of the place of his sojourn fits the description of the area, which is quite different to any other part of Australia.

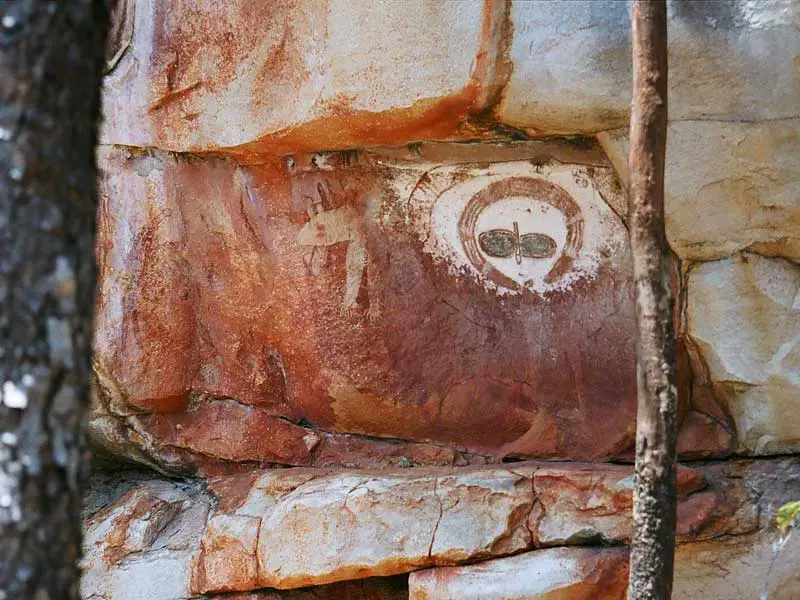

Lieutenant George Grey explored the Kimberley region in 1838 and his description of the natives, their customs, tribal structure and way of life, is not dissimilar to that described by De Gonneville. Further, Grey discovered a series of caves containing what we now know as the Wandjina figures, that he observed were unlike any currently being drawn by the local natives. Some of these figures rsembled nuns with head-dresses and beads, not unlike pictures common throughout contemporary Europe of the Virgin Mary surrounded by other women in an act of worship. Of one, he wrote, “Its head was encircled by bright red rays, something like the rays which one sees proceeding from the sun, when depicted on the sign board of a public house.”

Of another, he recorded, “It was the figure of a man, ten feet 6 inches [3.2 metres] in length, clothed from the chin downwards in a red garment, which reached to the wrist and ankles” “… The face and head of the figure were enveloped in a succession of circular bandages or rollers … these were coloured red, yellow and white: and the eyes were the only features represented on the face. Upon the highest bandage or roller, a series of lines were painted in red … it was impossible to tell whether they were intended to depict written characters, or some ornament for the head.” Grey’s writings are an accurate description of a priest dressed in his cassock. Grey also found there the head of an European sculptured in the hard rock, evidently with instruments such as the natives do not possess. The sculpture has never been located by subsequent visitors to the area.

To Grey the art in these caves was a strange mixture of European and Malay art; the former exhibited in the remarkable aureolas which so commonly surround the heads of saints in church windows at the time of De Gonneville; the latter depicted in the dress-like garmet over the body, which resembled the matted clothing of Malay peasants (Malay fishermen were known to have made regular fishing trips to the area).

In the tribal history of Aborigines living in the vicinity of Napier Broome Bay on the far North Eastern coast of Western Australia, is the story of how two Portuguese swivel guns named carronades were taken after a battle with white-skinned invaders dressed in skins like those of turtles and crocodiles, a description of European armour. The tribal elders, using the number of past generations to calculate the passage of time, estimated that the intruders were seen about l550 AD, which coincides with De Gonneville’s claimed visit to the South Land.

It is well documented that Aborigines in all parts of Australia, on first meeting white people, commonly mistook them for spirit beings. Their common reaction, like lighting fires and throwing stones, was consistent with their method of driving spirits away. If De Gonneville did land on Australian soil, by the description he gave of his landfall he could have landed nowhere else but at precisely that part of the country visited and similarly described by Grey. The paintings Grey discovered, which today are known as Wandjina, may well relate to De Gonneville and his companions and their practicing of Catholicism during their six month sojourn in the Kimberleys.