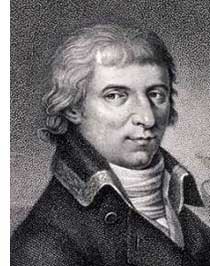

Baudin was born at Port La Rochelle, a seaport town on an island off the west coast of France, the fifth child in his family. At age 15, Baudin went to sea as a cabin boy, and when 20, after being a Naval Cadet for 12 months he looked to the French East India Company for a career. In a troop transport en route to India he became a quartermaster, but lasted only two years before disillusionment found him back in France.

Baudin was born at Port La Rochelle, a seaport town on an island off the west coast of France, the fifth child in his family. At age 15, Baudin went to sea as a cabin boy, and when 20, after being a Naval Cadet for 12 months he looked to the French East India Company for a career. In a troop transport en route to India he became a quartermaster, but lasted only two years before disillusionment found him back in France.With France entering the American War of Independence, he joined up as an Officer, to serve in the Caribbean for a year, then taking command of the sloop Apollon on convoy duty in the English Channel. But once more he was frustrated, when a Nobleman outranking him, grabbed his position as commanding officer, and Baudin quickly resigned to work abroad in the merchant service. He rose to command voyages, emigrants to New Orleans, back loading timber for Nantes, at last his fortunes started to improve. He took Franz Boos, the Austrian Emperor's head gardener on board, and now made a series of botanical expeditions for the Austrians, over 5 years he undertook three voyages to the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Boos taught him about botany, and how to care for animals and plants, during one trip ostriches, zebras, plants and seedlings were all carried and nurtured.

On the day in April 1792 that France went to war against Austria, Baudin had sailed, at his first port of call he tried to rejoin the French Navy, he was not accepted, and the Imperial Ambassador at Madrid learnt about it all, Spanish authorities took over Baudin's ship, and threw him into prison. In the interim, many of his crew left the ship, even after he was released from prison many of his officers were upset by Baudin's actions and resigned. Baudin continued on to the Cape, took Scholl and his collection of Flora and fauna onboard and set sail for New Holland. Baudin and his ship, Jardiniere III were driven northwards by hurricane winds and he was forced to enter Bombay to undertake repairs. But Baudin was unaware that France was also at war with Britain, and he had more crew leave him and the ship, he took on some Indian seamen to fill the gap. Now he gave up any plans to sail to the Far East, and made for the area of the Red Sea and on to East Africa. He obviously had no qualms about the Slave Trade, taking on board slaves from African ports.

As he sailed south to enter Table Bay at the Cape of Good Hope, he again ran into storms, but this time they drove his vessel aground. This became a failed voyage, and Scholl who had been trying to leave the Cape area for some 8 years, now blamed Baudin, he thought the Captain had deliberately put his ship aground so he could dispose of the black slaves. The movements of Baudin after the stranding of his ship are not well documented, he apparently saved a collection of plants and trees from the shipwreck, because he took them to his botanist friend Labarrere at Trinidad. Baudin turned up in the United States, gained a passport from the French Ambassador and via an American ship returned to France.

He now played his experience as A Botanical Voyager card, visiting the Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris to lobby Professor Antoine-Laurent Jussieu, within six months the professor and his staff had convinced the Government to charter a small ship to sail to Trinidad to recover the botanical collection left there by Baudin. The Museum chose four scientists to join with Baudin for this trip. This ship, Belle-Angelique set off from Le Havre, and Sir Joseph Banks recommended that this expedition be given safe conduct by the British, very important, recalling that the two countries were at war. After three weeks at sea, the ship ran into a howling gale blowing in from the west, it took all of Baudin's skills as a seaman to save his ship, as he put into Tenerife. Belle-Angelique would sail no more, and her Captain now got hold of a smaller vessel and made for Trinidad, but on arrival, the British would not allow him to land.

Off he went to one of the Virgin Islands, St Thomas, now a Danish colony, the four scientists went fossilling in the volcanic rich area, and Baudin acquired a larger ship, renaming her Belle-Anglique after her namesake. After a 10 week sojourn, the ship moved onto San Juan, and over 9 months Baudin and his party gathered up plants, birds, insects, samples of different species of wood, all in all, a mighty collection from the West Indies. On his way home to France, Baudin was stopped by an English warship, and interrogated on board, in case of his dentention, he prudently told the British Commodore " It would have reflected more glory on you to show favour to an expedition undertaken for the progress of science." He was released, to safely deliver the collection to Paris, which became part of a parade through that city, the crowds amazed at wagons bearing banana and coconut palms, paw paw trees, and many other exotic plants unknown in Europe. As designed, Baudin had made his name, was reinstated into the French Navy, and promoted to Post Captain.

In 1800 Baudin was still trying to mount an expedition to tour the world, he wanted to go to the Americas, the Islands of the Pacific, New Holland and the southern parts of Africa, and Baudin appealed directly to General Bonaparte, the leader of the young Republic. Important men such as Jusseiu, Fleurieu and Bouganville all backed this plan, the latter had been the first European explorer to actually sight the Great Barrier Reef off the Australian coast, but his crew were weakened by both scurvy and sickness, and Bouganville had been unable to explore this marvel.

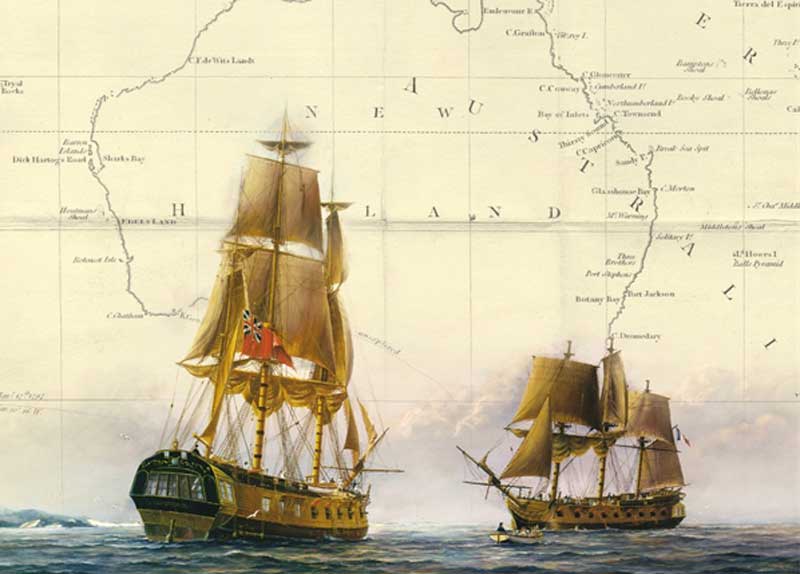

Bonaparte agreed to a less ambitious expedition, two ships under Baudin would explore the coast of New Holland and the southern part of New Guinea. The Republic had wanted for some time to make good the French claims to Southern Australia ahead of the British, from Western Port to Nuyt's Archipelago, which they called Terre Napoleon, and saw Baudin's expedition as a means of finding out whether such a action would be of benefit to France.

The two ships were the 30 gun corvette Geographe, drawing about 15 feet of water, and having the reputation of being a "Fine sailer" but perhaps not as sturdy a ship as needed for a journey across the world's oceans. Her companion ship, Naturaliste, in contrast, a large and strongly built store ship, with a draught similar to Geographe, but with much lesser sailing qualities, which would prove to become quite a problem, as the two ships were to become separated twice during the forthcoming voyage, to cast some doubts on Baudin's reputation as a competent Navigator.

Baudin wanted eight officers and 92 crew, plus eight scientists aboard each ship, but on sailing, Geographe, under Baudin, had 118, whilst Naturaliste, under Jacques-Felix-Emmanuel Hamelin (1768-1839), had 120, plus 11 extra seamen who had managed to sneak onboard. On board Naturaliste was Sub-Lt Louis De Freycinet. Overcrowding was soon a problem for the total of 251 aboard these two ships. Important families had lobbied for their sons, nephews, or proteges to join the expedition, and Bouganville had managed to get his 18 year old son a berth, who proved to be quite useless, leaving the journey along with other officers and young gentlemen. Although Baudin only wanted eight scientists for each ship, he was saddled with twenty three astronomers, landscape and portrait artists, geographers, minerologists, botanists, zoologists, gardeners, naval surgeons and a pharmacist.

Encounter Bay

By the time the ships reached Isle de France, the gilt had worn off the expedition for ten of this group, pleading ill health, they left, and Baudin was happy to see them go. He took along in their place two talented illustrators, Charles-Alexander Lesueur and Nicolas-Martin Petit. It was May 1801, before his two ships made a landfall at Cape Leeuwin on the south west corner of Australia, he now spent three months charting the coast of Western Australia and gathering scientific data, but he needed to visit Timor to replenish his ships. He now sailed to the southern parts of the continent, giving many places French names, he called this land Terre Napoleon after his Emperor and approver of his expedition. The east coast of Tasmania was explored, and in April of 1802, he made his now famous meeting with Matthew Flinders at Encounter Bay on the South Australian coast, he was sailing eastwards, whilst Baudin was making westwards, what a chance in millions that these two intrepid, but totally different Navigators, should meet up here in the wild waters south of Australia. Surely one of the most unlikely and historic meetings of all time.

Flinders and Baudin at Encounter Bay

Many of Baudin's company were very ill with scurvy, and he sailed his ships to Botany Bay, seeking the hospitality of Governor King and the English colony, the French were well received, offered medical attention, and provisions, both sorely needed. After recuperating at Port Jackson under the patronage of the beleaguered Governor King, Baudin was keen to continue his explorations. Naturaliste had proved a poor sailer, however, and it was sent home under Hamelin with the expedition's collections and works. A small locally-built schooner Casuarina was purchased in its stead and Freycinet was elevated above others, including his brother Henri, to command.

In continuing along the south coast via Tasmania and then back up the west coast with Baudin in Geographe, Freycinet was a to complete the surveys for many fine charts. These included the Gulfs in southern Australia, the south of western Australia, the mid west, notably Sharks Bay, and Dampier and the Institut Archipelagoes further north. In November 1802, Baudin sailed again, around the southern coastline, up the west coast, once more to Timor. He then he set off for Isle de France (Mauritus), arriving to be quite sick with tuberculosis, Baudin died here in September 1803, only a few weeks before the arrival of his great rival Navigator, Matthew Flinders, who was imprisoned by the French authorities.

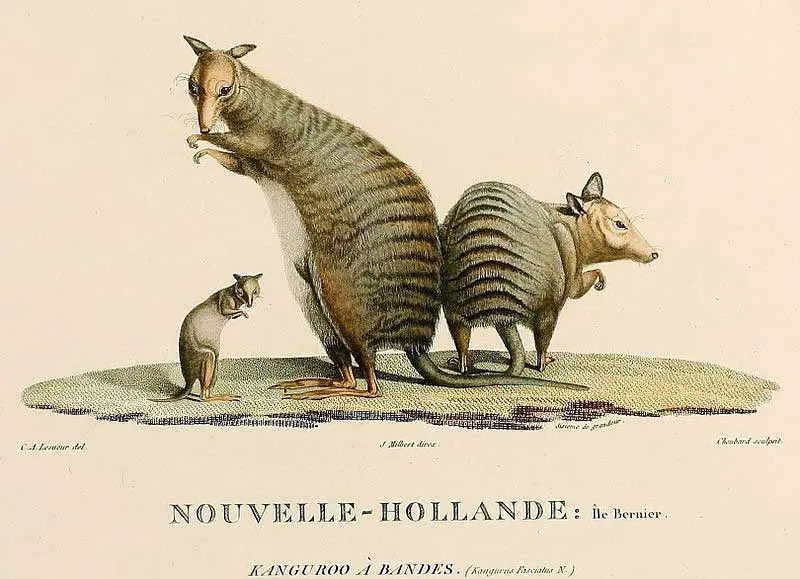

Baudin is said to have been shunned by Napoleon because of his failure to claim South Australia for France before Matthew Flinders did. Baudin is said to have been detested and reviled by his officers and staff and also that he died in disgrace. Francois Peron, who wrote the history of the voyage, particularly hated him. He portrayed Baudin as malicious, venal and incompetent. Baudin deserves more credit and recognition than that. The Baudin led expedition had been important in unfolding mysteries about Australia, its Aboriginal people, its fauna and flora, and is remembered for his contribution to scientific knowledge, and his unrelenting quest for seeking new horizons. Their discoveries included some 1500 botanical and 3900 zoological species. That was apparently more specimens and more species new to science than all previous European voyages combined.

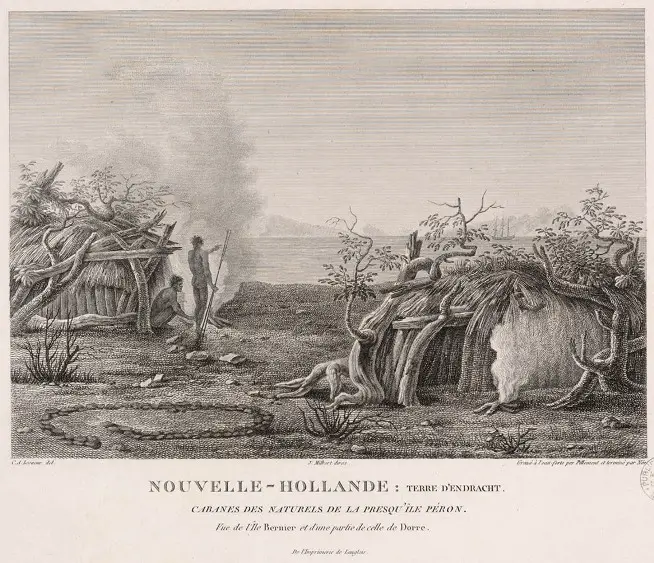

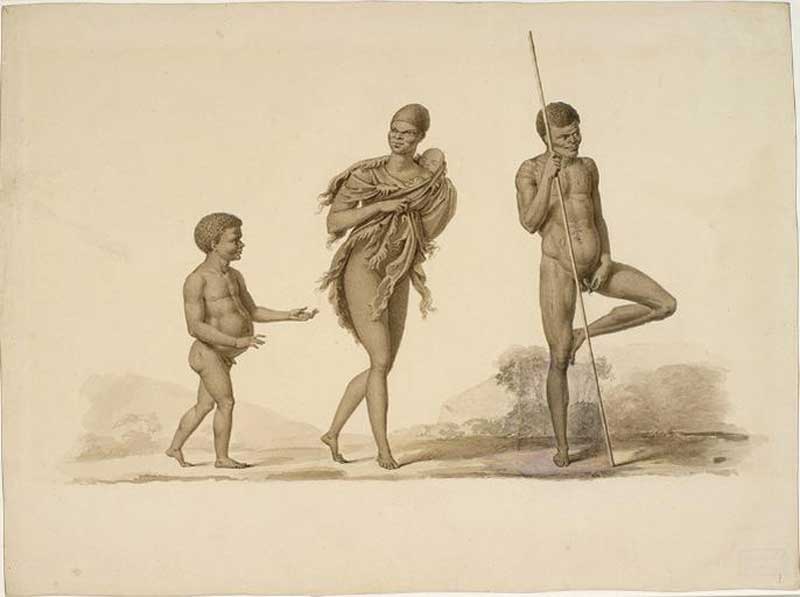

Despite the opposition from scientists, many of the plant and animal specimens collected on the voyage and returned to France found their way to the Empress Josephine's garden at Malmaison. There they proved an object of continual fascination as this illustration showing swans, emus and Australian flora at Malmaison on the banks of the Seine indicates. Many specimens were also beautifully illustrated, especially by Pierre Redoute, who also had earlier presented the works of the D'Entrecasteaux expedition to the world. The expedition's assistant gunners Charles-Alexandre Leseur and Nicolas-Martin Petit also stunned Europe with their illustrations of the people and the animal life. Despite publication in Europe, these works and the collections are only now become generally known in Australia, in this year 2001, the Australian Bicentennial of Baudin and Hamelin's visit.

Banded hare-wallabies of Bernier Island; illustration by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur.

Banded hare-wallabies of Bernier Island; illustration by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur.

It is fair to say that their images of the flora, fauna and of the Aboriginal people changed the perceptions that followed on from the Dutch and from William Dampier's widely disseminated and predominantly negative reactions to the land and its peoples. That they had a significant and long lasting effect in France is indicated two decades after the voyage when Rose de Freycinet's mother, in advising Rose when she too expressed negative reactions to the people encountered in New Holland that she need 'look at the drawings in Baudin's voyage & and you will have a true idea of these people'.

Thus in the wake of the Dutch and Dampier, the west coast of New Holland and the south and south west coasts were expertly mapped in expeditions led by the French explorers D'Entrecasteaux in 1792, and Baudin in the period 1801-1803. Many places on these coasts now bear French names in honour of expedition members or their supporters, and Louis de Freycinet was an integral part of it all. His Cartes General de la Nouvelle Hollande and Cartes General de la Nouvelle Hollande de la Terre Napoleon, and Carte de la Baie Des Chien-Marins, Sharks Bay de Dampier, are especially notable.

Terre Napoleon, the name given to the entire eastern south coast, did not survive colonisation by the British or the subsequent examination of Flinder's charts, however. These, like together with the unfortunate hydrographer/explorer himself remained in French hands for six years after his imprisonment at Ile De France in 1804. Despite this, Flinder's names have since prevailed over many of the French and it is also now generally accepted that it was he who, in earlier proving that the land mass was one, named the island continent Australia.

It is interesting to reflect at this juncture on the British retention of Beautemps-Beaupre's charts of the D'Entrecasteaux voyages until 1802 to the detriment of Baudin and his cartographers and on the French retention of Flinder's and his charts for a similar length of time until 1810 with the reverse effect for those Britons who followed him. Baudin also reported quite unenthusiastically on the land and for over a decade after the Baudin voyages French interest in the Great Southland waned, partly because of Napoleon's focus on Europe, and the proximity of the British on those parts of the east coast that the French desired. Mauritius (Ile de France) then became the French base in the Indian Ocean. After Trafalgar in 1805 and the British occupation of Mauritius five years later French naval power in the Indian Ocean had all but evaporated.

Louis de Freycinet

Lesueur was born in Le Harve, France on 1 January 1778. His family were not particularly well off but Lesueur was able to attend the School of Hydrography were he learnt draughtsmanship and applied graphic techniques. His work was so impressive that Commander Baudin commissioned him personally for the voyage. He in fact enlisted as an assistant gunner and assumed that he would not have to do any of the normal jobs on board ship. He was on board to draw. Lesueur and another young artist Nicholas-Martin Petit were employed for the main job of illustrating Baudin's log-his record of the journey. They must have created quite an impression because their work quickly overshadowed the work of the official artists of the expedition who resigned when Le Geographe and Le Naturaliste stopped over at Mauritius. From that time on the two younger inexperienced artists were officially recognised and would join the scientists on their explorations once New Holland was reached.

Lesueur was born in Le Harve, France on 1 January 1778. His family were not particularly well off but Lesueur was able to attend the School of Hydrography were he learnt draughtsmanship and applied graphic techniques. His work was so impressive that Commander Baudin commissioned him personally for the voyage. He in fact enlisted as an assistant gunner and assumed that he would not have to do any of the normal jobs on board ship. He was on board to draw. Lesueur and another young artist Nicholas-Martin Petit were employed for the main job of illustrating Baudin's log-his record of the journey. They must have created quite an impression because their work quickly overshadowed the work of the official artists of the expedition who resigned when Le Geographe and Le Naturaliste stopped over at Mauritius. From that time on the two younger inexperienced artists were officially recognised and would join the scientists on their explorations once New Holland was reached.

As the journey progressed Lesueur became more of a specialist in drawing animals. This is because he became very close friends with the zoologist Peron. Peron was disliked a great deal by Baudin and made many enemies during the voyage. However, he and Lesueur became firm friends. Under Peron's guidance, Lesueur learnt the art of taxidermy, and the skills for trapping and hunting animals. At other times Peron would dance about and play the fool to distract the Indigenous Australians while Lesueur sketched them. Lesueur also learnt from Peron the importance of colour and paying particular attention to detail. Apart from completing drawings of many animals, he produced a variety of landscapes often including aspects of Indigenous Australian culture.

Life was obviously very hard on board ship. Sickness was a big problem that faced the Baudin expedition, especially scurvy and dysentery. Just like the Flinders's expedition, Baudin stopped over in Timor, resting up at Kupang on 21 August 1801. Many of the crew were ill from scurvy or from dysentery (probably from the water supply on board ship). Baudin himself came down with Malaria. Lesueur was not spared either. He was bitten by a snake while chasing after some monkeys and became very ill. Can you imagine the kind of first aid that would have been used on him? After a large piece of his flesh was removed and the wound dressed, he was miraculously nursed back to health.

Upon completion of the expedition Lesueur returned to France in 1804. He and Peron set about the task of publishing the results of the expedition. When the two presented their large and impressive collection the professors at the Museum d'Histrorie Naturelle in Paris were very excited. In a crowded apartment near the Museum the two friends spent their time cataloguing specimens and getting their living plant and animal specimens used to living in a new country. Lesueur worked on producing watercolours from the sketches he had done in Australia. He exhibited some of them at the Museum in the hope that he might gain the place as their resident artist but he was not successful.

In 1806 the Emperor Napoleon himself gave permission for Lesueur and Peron to publish their findings in a Journal to be called Voyage de decouvertes aux Terres Australes, written by Peron and illustrated with forty plates by Lesueur. They were issued a pension or salary to support them as they worked on it The first volume appeared in 1807, which included many of Lesueur's drawings. Before the second volume was completed, Peron took ill and died in 1810. The directorship of the project was taken over by Louis de Freychinet, the map maker and surveyor who had been aboard the Naturaliste. The second volume was eventually published in 1816.

After the fall of Napoleon and the collapse of his Empire in 1815 Lesueur must have been worried that he would lose his pension. Having published a few articles in scientific magazines between 1813 and 1815 Lesueur joined the geologist William Maclure on a study tour of the United States of America. He ended up staying there for twenty two years. His journeys took him from the islands of the West Indies to the Great Lakes of North America. During his stay in the United States his reputation grew. He studied mainly fish and tortoises and published many articles in the Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. He even had a go at living on a commune on the banks of the Ohio River! Lesueur was one of the pioneers of lithography (the art of writing or drawing on stone, and of printing the impression on paper) in the US.

He returned to France in 1837. After some extremely well received results of a study he made of the geology of the cliffs around Le Harve, Lesueur began to receive a lot more credit and praise. In 1844 he received the silver medal from the Societe libre des Beau-Arts in Paris. In recognition of a lifetime devoted to scientific research he was appointed Chevalier de l'Order de la Legion d'Honneur and the city of Le Harve offered him the job as Museum curator where he had donated half of his collection.

Lesueur died suddenly on 12 December 1846. He is widely regarded as a first class natural history painter. Although most of his taxidermy and jarred specimens from his exploration were destroyed during WW2 all of his artistic work remains intact at the Museums d'histoire naturelle in Paris and Le Harve.

Peron was born in Cerilly in 1775, the son of a harness maker. He enlisted in the revolutionary army in 1792 and was taken prisoner. During this time he lost an eye but he was able to return home safely in 1794. He began studying medicine but when he heard of the Baudin expedition he pestered long and hard to be included as part of the scientific team. Baudin's expedition was much larger than Flinders's. There were two ships, Le Geographe and Le Naturaliste, a team of twenty two civilian scientists, anthropologists, botanists, mineralogists and natural history artists to name but a few. Both ships carried a huge amount of equipment for measuring, collecting, drawing and storing. Napoleon's France had a much grander vision for this expedition than the British had for the Flinders journey. However, bad luck and terrible sickness plagued the expedition all the way and it didn't end up quite the way that had been planned.

Peron was born in Cerilly in 1775, the son of a harness maker. He enlisted in the revolutionary army in 1792 and was taken prisoner. During this time he lost an eye but he was able to return home safely in 1794. He began studying medicine but when he heard of the Baudin expedition he pestered long and hard to be included as part of the scientific team. Baudin's expedition was much larger than Flinders's. There were two ships, Le Geographe and Le Naturaliste, a team of twenty two civilian scientists, anthropologists, botanists, mineralogists and natural history artists to name but a few. Both ships carried a huge amount of equipment for measuring, collecting, drawing and storing. Napoleon's France had a much grander vision for this expedition than the British had for the Flinders journey. However, bad luck and terrible sickness plagued the expedition all the way and it didn't end up quite the way that had been planned.

Baudin selected Peron at the last minute as the expedition's field anthropologist (but served also as a zoologist) and ended up disliking him intensely. In fact on the eve of the voyage Peron described himself as being argumentative, difficult to get along with, a know-all and a maker of enemies! As it turned out, Peron disliked Baudin just as much. Both men wrote journals about the expedition and both men have a go at each other throughout the books. Peron accuses Baudin of being obstinate, full of fault, a wretched tyrant, an oaf, a fool and utterly incompetent as a sailor. Peron blamed Baudin for all the problems that the expedition encountered, even those that were clearly out of Baudin's control. Ironically, though it was Baudin's responsibility to select the names for coastal features being named by the expedition, Peron ended up as the expedition member with the greatest number of Australian coastal features named in his honour.

Peron Peninsula, Shark Bay, Western Australia

Baudin's task was to explore and map New Holland or Terra Australis as it was also known. The British had already established a convict settlement on the east coast at Port Jackson. At the time both Empires were suspicious of each other. The French wanted to chart and map the far west and southern coasts of the continent for scientific purposes but also with the possibility of laying claim to some of it. Both France and the British Empire had possession of islands and territory in the Pacific Ocean region and New Holland would make an ideal base to keep watch on their possessions and each other. On Flinders Investigator, there was only one botanist, Robert Brown whose main job was to collect plant specimens. Peron was part of a large team and he had many jobs to do. His studies on the voyage included anatomy, anthropology, botany, zoology, meteorology, oceanography and naval hygene! He even took it upon himself to write about the British settlement at Port Jackson., He mentioned the strengths and weakness of the British in the region and even suggested a way to mount an invasion of Port Jackson using Irish convicts!

Life was obviously very hard on board ship. Indeed as the ships were sailing to their destination in November, 1800, tempers flared and fights erupted. When the ships called in at Mauritius in 1801 many of the scientists and artists left the expedition. Sickness was a big problem that faced the Baudin expedition, especially from scurvy and dysentery. In fact of those scientists and artists who remained with the expedition when it left Mauritius for New Holland only seven survived the journey. It therefore fell to the junior members of the expedition, namely Peron, Lesueur and Petit (zoologist, natural history artist and landscape artist respectively) to take on the roles of official scientific researchers and recorders. Peron became the senior zoologist.

New Holland: New South Wales. Spotted-tail quoll. "A Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Hemisphere" by Francois Peron and Louis Freycinet. L'Imprimerie Imperiale, Paris 1807-16. Charles-Alexandre LESUEUR. Jean Dominique Etienne CANU

On the voyage Peron and Lesueur became lifelong friends and colleagues. Lesueur began the expedition as an merely an artist but under the guidance of his new friend he developed many extra skills. Peron instructed Lesueur in scientific, zoological and botanical studies. He taught him the art of taxidermy and how to hunt and trap animals. Through Peron, Lesueur perfected the use of colour and precise attention to detail in his drawings. Peron took it upon himself to study the tiny soft marine creatures of the Australian waters. At King George Sound he collected some 1060 new species of seashells and a vast collection of starfish. Lesueur was always at the ready with brush and many of the images he captured remain deeply admired and treasured today. Encouraged by Peron, Lesueur draw a wide range of Australian animals in strict scientific pose and detail. These include emu from Kangaroo Island (believed to be an extinct species), platypus, fish and frogs. Many species of birds and animals were trapped and killed and put into specimen jars filled with alcohol to preserve them.

Peron proved to be a great help to both Lesueur and Petit as they tried to make drawings of Indigenous Australians. He would dance about and play the fool to cause a distraction while the artists quickly drew their subjects. The Indigenous Australians were mostly cooperative but at times they did get fed up and even angry with the Frenchmen. Several times pistols and muskets had to be raised. Petit narrowly escaped being clubbed by an extremely angry Indigenous Australian. He had made a grab for the sketches that Petit had drawn On another occasion Peron had a long hat pin driven into his leg by an Indigenous Australian. At the end of the expedition Peron and Lesueur had collected what is considered to be most complete and best documented collection of marine natural history. Over one hundred thousand species of animals had been collected and stored in thirty three large packing cases aboard Le Naturaliste.

Upon completion of the expedition Peron and Lesueur returned to France in 1804. They set about the task of publishing the results of the expedition. When the two presented their large and impressive collection, the professors at the Museum d'Histrorie Naturelle in Paris were very excited. While the professors were excited Napoleon appeared to have lost interest in the project. There was some delay in actually getting down to work and publishing the findings in writing. Finally in late 1804, in a crowded apartment near the Museum, the two friends spent their time cataloguing specimens and getting their living plant and animal specimens used to living in a new country. Lesueur worked on producing watercolours from the sketches he had done in Australia. He exhibited some of them at the Museum in the hope that he might gain the place as their resident artist but he was not successful.

In 1806 the Emperor Napoleon himself gave permission for Lesueur and Peron to publish their findings in a Journal to be called Voyage de decouvertes aux Terres Australes, written by Peron and illustrated with forty plates by Lesueur. They were issued a pension or salary to support them as they worked on it. The first volume appeared in 1807, which included many of Lesueur's drawings. Peron also worked on a journal of the expedition called Memoire sur les establissements anglais a la Nouvelle Hollande. In this journal he combined accounts of the scientific work that was done, harsh criticism of Baudin and full and flowery praise for himself! Before the second volume of Voyage? was completed, Peron took ill and died of tuberculosis in 1810. The directorship of the project was taken over by Louis de Freychinet, the map maker and surveyor who had been aboard the Naturaliste The second volume was eventually published in 1816.

Peron is described as the first informed zoologist to land in Australia. He collected an enormous amount of material and his extensive fieldwork and attention to detail was ahead of its time. The extensive collections of Peron and Lesueur remained undisplayed in the Museum national d'histoire naturelle Paris along with all the meticulous recordings of animal specimens. It wasn't until 1846 that Lesueur finally got hold of his drawings and Peron's materials. From the time of Baudin's expedition, nearly two hundred years would pass before a visual record of the work of Peron and Lesueur was brought to public view.

Petit was born in June 1777, the son of a fan maker. He was born during the period of the French Revolution and then grew up during the rise of Napoleon and the growth of the new French Empire. Napoleon was a military leader who wanted to conquer other countries. He required a large army for this so young men were drafted or conscripted into the army. This meant they had no choice, they had to enlist. However, if young men could prove themselves to be unfit for military service they could get out of it. Sometimes they simply avoided turning up when required. It seems that this is what Nicholas-Martin Petit did.

He attended the School of David in Paris and studied graphic arts. He was trained by Napoleon's portrait painter, Jacques Louis David. It seems Petit did not answer his conscription order. In 1800, Post-Captain Nicholas Baudin was commissioned by the French government to undertake a scientific voyage of discovery to the Australian continent known then as New Holland. The French were very keen to explore and map this relatively unknown continent. The British had already established a convict settlement on the east coast at Port Jackson. Both Empires were suspicious of each other. The French wanted to chart and map the far west and southern coasts of the continent for scientific purposes but also with the possibility of laying claim to some of it. Both France and the British Empire had possession of islands and territory in the Pacific Ocean region and New Holland would make an ideal base to keep watch on their possessions and each other.

Primarily, scientific discovery, exploration and map making were the main areas that Baudin was concerned with. He hoped to bring back riches of a scientific nature, of plant and animal discoveries that would bring great prestige to France. All areas of science were to be explored and so Baudin found himself with two ships of varying size and speed and a large amount of crew, scientists, botanists and artists. Among them were the artists Charles-Alexandre Lesueur and Petit. Both were taken on board as assistant gunners but their duties were to draw. Petit and Lesueur were employed for the main job of illustrating Baudin's log-his record of the journey. They must have created quite an impression because their work quickly overshadowed the work of the official artists of the expedition who resigned when the Le Geographe and the Le Naturaliste stopped over at Mauritius. From that time on the two younger inexperienced artists were officially recognised and would join the scientists on their explorations once New Holland was reached.

As the journey progressed Petit began to specialise in the drawing of portraits of indigenous peoples the expedition encountered. Lesueur focused on animals. Petit's art included portraits and scenes from Australia, South Africa, Timor and Tenerife. Petit must have been a bit of a cheeky character. He would often delight his team members by producing caricatures of expedition members and of other people they met along the way.

Nicolas-Martin Petit, "Personnages de la Terre de Diemen (Tasmanie)"

Petit's drawing of Indigenous Australian's especially those from Tasmania "remain a rare and precious account of the actual lifestyle of the Aborigines at the beginning of the nineteenth century & " It did prove difficult at times to draw the Indigenous Australians. He would mimic them and strike poses himself and urge them to copy him. Petit wanted theatrical poses not natural ones and his antics must have surprised the Indigenous Australians. He was helped by the botanist Peron who too would play the fool and distract the Indigenous Australians while both Petit and Lesueur quickly got their sketches down.

At times Petit's behaviour irritated the Indigenous Australians and some situations became dangerous. On one occasion on Maria Island, just off the south east coast of Van Dieman's Land (Tasmania) Peron had a long hat pin stuck in his leg and one of his ear rings torn from his ear. After a long day the Indigenous Australians had had enough of Petit's demands and Peron's silliness and rushed Petit and his companions with raised spears. With raised muskets and shouts of warning the Frenchmen were able to get back into their rowboat and to safety. During another incident in the south of Van Dieman's Land, an Indigenous Australian rushed at Petit to snatch away his sketches and threatened to attack him with a log.

In 1803 on the second visit to Shark Bay in Western Australia, Peron led Petit and another man called Guichenot well away from the main group. Without food of water and armed with only two pistols and a musket, the three walked for hours in the scorching sun. They finally reached the far coast and were able to wade through the low tidal flat , cool down and collect the shells that Peron had been so keen to collect. When a fish brushed against Petit's leg he panicked thinking it was a shark and fired his pistol. Suddenly a band of naked warriors appeared from the bush and rushed towards the terror stricken Frenchmen. However, at the sight of the guns the Indigenous Australians held back and eventually walked off peacefully. A narrow escape!

Sickness was possibly the biggest problem Baudin's expedition faced. His expedition stopped over twice at Kupang, Timor in 1801 and 1803. On both occasions expedition members suffered from scurvy and dysentery and there were deaths. Baudin himself contracted Malaria in 1801 and became dangerously ill again there in 1803. Petit suffered several bouts of scurvy, dysentery and fever during the 1803 visit.

Petit returned to France in 1804, married and looked forward to settling down in Paris. He obtained authorisation form the Navy to complete his drawings for official publication. Unfortunately Petit was worn out and badly affected by scurvy. Before he was well enough to attempt to complete his drawings from the expedition he hurt his knee. It became gangrenous and he died tragically at the age of 28. Petit's unfinished work was published in 1807 in the Atlas of the Voyage de decouvertes aux terres australes. Today most of his drawings are kept in the Museum d'histoire naturelle, Le Harve. Baudin's private log, which is kept at the Centre Historique of the Archives Nationales in Paris, contains many of Petit's coastal profiles.