Replica of the Duyfken

To the 17th Century world, Australia was very much an unknown quantity. On the maps in use at the time, it was marked as Java Le Grande and believed to be a land full of gold, spices and precious metals. During the heady days of European colonial expansion, it was seen as the ultimate acquisition, yet it eluded navigators for decades, mainly because the method of calculating longitude was so inaccurate the island continent was not where it was believed to be. Some 164 years before Lieutenant James Cook sighted Point Hicks and began charting the East Coast of Australia, the Dutch made the first officially recorded sighting of the mainland of Australia by Europeans, though they believed it to be a continuation of the New Guinea coast, having missed sighting Torres Strait which separates them. What they saw was in fact a section of the coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria and east coast of Cape York. Their leader was Willem Janszoon (William Janz), who shared command of a small vessel called the Duyfken with Jan Roossengin, a merchant-official of the Dutch East Indies Company on an expedition which left Batavia for the coast of New Guinea in 1606.

Janz's discovery came about not by accident, but by design. His orders were to search for the south land beyond the southern shores of New Guinea. This he did, but his voyage was marred by numerous clashes with natives of both New Guinea and the Australian mainland. Many of Janz' men were injured in the clashes, and one was speared to death, becoming the first recorded death of a European on Australian soil. With his crew depleted, Janz turned back, naming his point of departure Cape Keerweer (Turnaround), and in doing so, became the first European to give an Australian coastal feature a name still in use today. Janz's dismal report led to the abandonment of further exploration by the Dutch in the area.

Replica of the Batavia

The entrance of the Dutch into the East as explorers, colonists, and merchants was connected with European events of very great importance. The Reformation was principally an affair of churches and forms of religious belief, but it also had far-reaching consequences touching politics, commerce, and all the manifold interests of mankind. Its influence extended throughout the known world, and led to the discovery, exploration and settlement of regions hitherto unknown.

During the third quarter of the 16th century Philip II of Spain was engaged in a bitter, bloody struggle with his subjects in the Netherlands. Thousands of them broke away from the ancient Holy Roman Catholic Church of which he was a devoted champion. Philip, loathing heresy, set himself to 'exterminate the root and ground of this pest,' and his ruthless Spanish soldiery carried out their master's injunctions with such pitiless ferocity that their effort to crush the revolt stands as one of the most awful phases of modern history. For over thirty years the Spanish sword was wet with the blood of the people of the Netherlands. In the southern provinces of Brabant and Flanders, Protestantism was suppressed; but the north, Holland and Zealand successfully defied the gloomy, conscientious fanatic who issued his edicts of persecution from Madrid.

The Dutch people at the time of the revolt did the largest sea-carrying trade in Europe. Their mercantile marine was numerous, and was manned by bold and skilful sailors. A very considerable part of their commerce consisted in fetching from Lisbon goods brought by the Portuguese from the East, and distributing them throughout the continent. It was a very profitable business, and it quite suited the Dutch that the Portuguese - the enemy of Spain - should enjoy a monopoly in Oriental trade as long as they themselves kept the major part of the European carrying trade. The Dutch grew rich and increased their shipping, and the growth of their wealth and sea-power enabled them the better to defy Philip II.

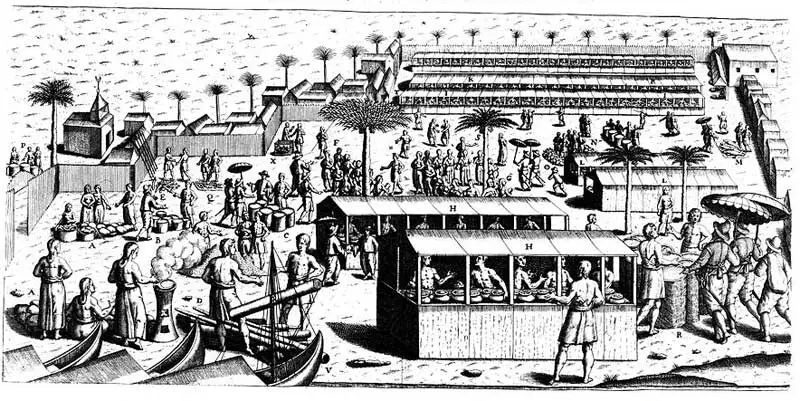

Bantam marketplace, c. 1607

Failing, therefore, to subjugate the Dutch by sword and cannon, Philip resolved to humble them by stifling their trade. In 1580 the throne of Portugal had fallen vacant, and a Spanish army which crossed the frontier had forced the Portuguese to accept Philip as king. For sixty years to come - until the Portuguese regained their independence in 1640 - the gallant little country of Portugal which had achieved such glorious pre-eminence in commerce and discovery remained in 'captivity' to Spain. The control thus secured by Philip over the colonies and the shipping of Portugal enabled him to strike the desired blow at the Dutch. In 1584 he commanded that Lisbon should be closed to their ships. Barring them entry the port whither came the goods from which they had derived such abundant gains, he sought to chastise them for their disobedience. But Philip wholly underestimated the spirit and enterprise of the Dutch people. In the past, they had baffled the best of his generals, beaten the choicest of his troops, and captured his ships upon the sea. They were now prepared to scorn his new menace by fetching direct the commodities which they had hitherto obtained from Lisbon. First they tried to find a new route to the East by a passage north of Europe, but were blocked by the ice of the Arctic Sea. If they were to succeed they must force their way into the trade by the Portuguese route in the teeth of Spanish opposition.

The Portuguese had tried to keep their sailing routes secret and had never published maps for general distribution, but they often had to avail themselves of the services of Dutch mariners; and these men knew the way. One of them, Cornelius Houtman, had actually been a pilot in the Portuguese Oriental trade. Another Dutchman, John Linschoten, had lived for 14 years in the East Indies, and upon his return in 1595, published in Amsterdam a remarkable book called Itinario, wherein he told all he knew. Several Englishmen had also wandered about the seas and lands of Asia, often having painful experiences, and their adventures had been described in Richard Hakluyt's Principal Navigations, Voyages And Discoveries, published in 1589. Thus the Dutch already knew more about the Indies than King Philip supposed, and they were ready to act boldly in putting their knowledge to practical uses.

Pelsart Island, Houtman's Abrolhos

A company of Amsterdam merchants fitted out a fleet of four ships, placed them under Cornelius Houtman's direction, and sent them on the first Dutch voyage to the spice islands. The journey there and back took two years to complete - from April 1595 to July 1597. Theirs were the first Dutch ships to round the Cape of Good Hope and to visit Madagascar, Goa, Java, and the Moluccas. Houtman and his brother Frederick became major players in the development of Dutch trade in the East.

Their name was the first of any Europeans to appear on the map of what became known as New Holland and would eventually be known as Australia - Houtman's Rocks, later known as Houtman's Abrolhos, was a long shoal of islands off the west coast of the continent. "Abri Voll Olos", from which the name is derived, was a Portuguese expression used by sailors of all nations, and literally meant 'open your eyes'. Iit was with this notation that Frederick marked his chartt when he came across the islands and shoals in July 1619. Sadly, numerous Dutch trading vessels failed to heed the warning would be wrecked on the reefs here.

In 1596 Houtman's pioneer fleet arrived at Bantam, West Java, and expelled the Portuguese. It was the first Dutch fleet to ply what became the East Indies trade route from Europe to the Far East via the Cape of Good Hope. Avoiding the Portuguese stronghold in the Malacca Strait, Houtman would sail the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra and began trade on the north coast of Java, establishing his base in Jakarta in 1619. From the seige of Jakatra in 1619 until 1949, when Indonesia gained it independence from the Dutch, Jakarta was known as Batavia.

In 1596 Houtman's pioneer fleet arrived at Bantam, West Java, and expelled the Portuguese. It was the first Dutch fleet to ply what became the East Indies trade route from Europe to the Far East via the Cape of Good Hope. Avoiding the Portuguese stronghold in the Malacca Strait, Houtman would sail the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra and began trade on the north coast of Java, establishing his base in Jakarta in 1619. From the seige of Jakatra in 1619 until 1949, when Indonesia gained it independence from the Dutch, Jakarta was known as Batavia.Houtman's voyage was a roaring financial success and led to a rush of fleets being assembled and dispatched from Holland. By 1602, so fierce was the competition, the States-General of the Netherlands ordered the establishment of the United East India Company, The Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), which saw the amalgamation of the major players into one united force in March 1602. The company's charter gave them exclusive use of trade routes, which meant the VOC also had a monopoly on exploration. Returning skippers lodged their charts and logs with the official cartographer of the company in Amsterdam, whose task it became, somewhat by default, to chart the west coast of Australia. For this reason it was first known as New Holland, though the Dutch never claimed possession of it or ever indicated a desire to.

Historic posts, Cape Inscription, Dirk Hartog Island

Hendrick Brouwer, commander of the Rode Leew (Red Lion) discovered in 1610 that, by remaining in the southern latitudes after rounding the Cape of Good Hope, he could take advantage of the Roaring Forties, the prevailing trade winds of the southern Indian Ocean, thereby reducing considerably the length of their journey over the traditional route which saw ships heading north or north east immediately after rounding the Cape. Though the VOC suspected that a great south land existed somewhere ahead of them, its coastline was believed to be much further west than it actually was, consequently they had no qualms about making Brouwer's new route to the Dutch East Indies the official route.

As the VOC captains took no precautions to steer their ships away from it, either by miscalculation of their position or by staying in the southern latitudes for too long, it was inevitabe that they would be blown onto the south land's western shores and its position finally determined and charted long before the rest of the country. The only question was who would be the first to sight it, and when. It did not take long, in fact the first one to site land, Dirch Hartichs (Dirk Hartog) of the Eendracht, was still sailing the high seas on his return voyage to the Netherlands where he would report his relatively uneventful encounter with the Australian coastline on his outbound voyage, when Brouwer's route was being officially adopted.

The Eendracht was part of a fleet which had set sail from Texel in the Netherlands on 23rd January 1616. Though the ship's log has since been lost, Hartog's personal letters indicate that, on 25th October 1616, he came across a string of uninhabited islands beyond which was a vast mainland. He went ashore on one of them - Dirk Hartog Island, named later in his honour - and high on the cliffs of Cape Inscription at Shark Bay, recorded his visit on a flattened pewter plate, which he nailed to a post before sailing away. The translation of the inscription reads: "On the 25th of October there arrived here the ship "den Eendracht" of Amsterdam supercargo Gilles Miebas of Liege; Skipper Dirck Hatichs of Amsterdam. She set sail again for Bantam on 27th do. Sub cargo Jan Stins; Upper steersman Pieter E. Doores of Bil. Dated 1616". A replica of the plate is on display at the WA Maritime Museum, Fremantle.

Hartog's plate was found by another Dutch sea captain Willem de Vlamingh on 4th February 1697, who replaced Hartog's plate with one of his own, which recorded both the earlier inscription, and his own visit to the location. The plate is on display at the WA Maritime Museum, Fremantle. The spot where the plates were mounted is marked today by a monument. The 81 years between their visits saw the arrival of a string of Dutch EastIndiamen to the inhospitable, rugged coastline. Some came ashore, didn't like what they saw and sailed on; most didn't bother to stop. A handful vanished on the journey to and from the Netherlands, the remains of which may one day be found in pieces on some lonely reef. Some, like the Trial (1622), Batavia (1629), Gilt Dragon (1656) and Zuytdorp (1702) came to grief on jagged rocks and reefs. Their stories are told in the next chapters which details the Dutch encounters of the Australian coastline.

1606 - 1619 1620 - 1650 1650 onwards

By the turn of the 19th century when the might of the Great Dutch East India Company had begun to wane, the Australian coastline from the North West Cape of NSW to the east coast of Tasmania had been added to the maps and charts of the world. As the majority of sightings and landings had been Dutch, the land inherited the name New Holland. Though the Dutch Government never bothered to validate the territorial claim of New Holland made by one of its navigators (it was also claimed by a Frenchman, but he was thrown into gaol for his actions!), it was seen as Dutch territory by the rest of Europe. This was acknowledged by Cook in 1770 when he claimed only that part of Australia up to the most easterly point of the coast recorded as having been visited by the Dutch. By the time the last Dutch EastIndiaman had been and gone, a large section of the map of the east coast of Australia from around Ceduna to the tip of Cape York had still to be filled in. It wouldn't officially appear on maps until after James Cook's voyage along the east coast in 1770.