Walter Burley Griffin’s Canberra

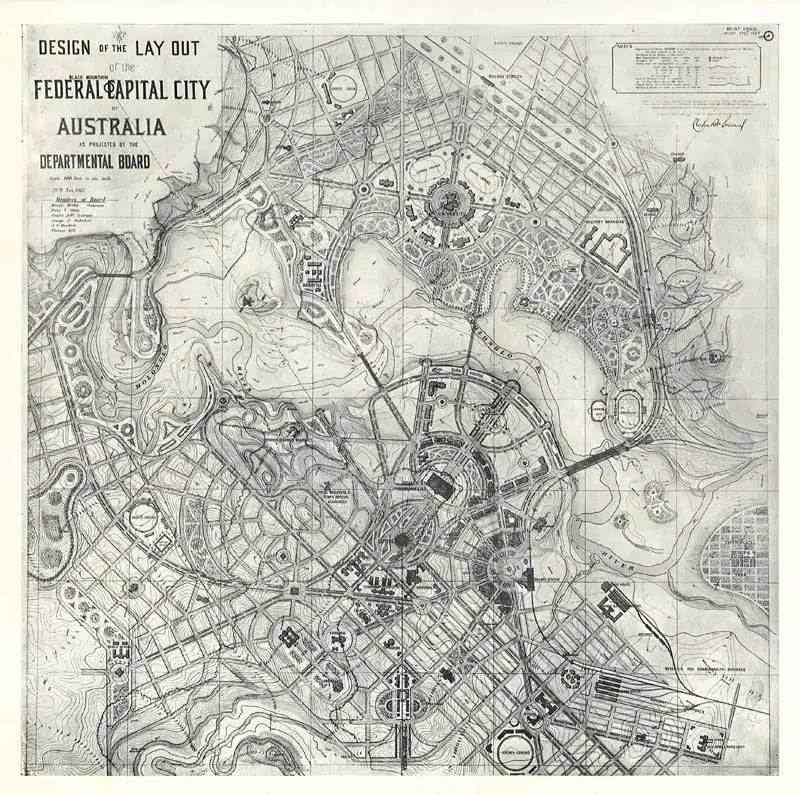

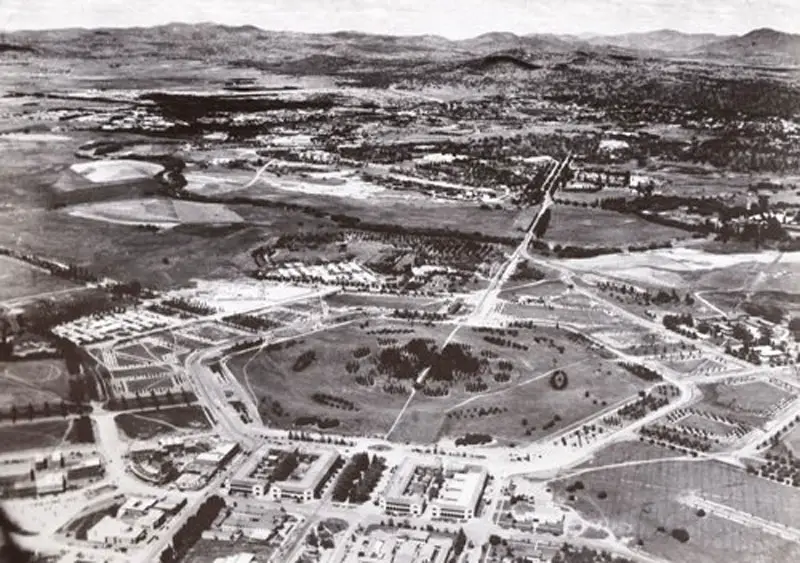

Canberra is unique among Australia’s capital cities in that it is the only one to have been built from the ground up to an overall master plan. An international competition was held in 1911 to select a plan for Australia’s capital city, after its location in the Monaro region of NSW on the Molongolo River had been decided upon. The competition was won by Chicago architect Walter Burley Griffin, who prepared his design with the help of his wife Marion, also an architect. Griffin’s design saw the heart of the city laid out around a large triangle on two major perpendicular axes, a water axis that today stretches along Lake Burley Griffin, and a ceremonial land axis stretching from Parliament House on Capital Hill north-eastward to the Australian War Memorial at the foot of Mt Ainslie. The area known as the Parliamentary Triangle is formed by three of Burley Griffin’s axes, stretching from Capital Hill along Commonwealth Avenue to the Civic Centre around City Hill, along Constitution Avenue to the Defence precinct on Russell Hill, and along Kings Avenue back to Capital Hill. Many significant public buildings such as the National Library and the High Court are located within this triangle.

The Burley Griffin design has now been altered significantly beyond the triangle, though within it, the most notable change is the location of Parliament House from the lakeside site Burley Griffin envisaged to Capital Hill, one of the axis points.

Canberra is divided into seven districts. In order of development, they are: North Canberra, South Canberra, Woden, Belconnen, Weston Creek, Tuggeranong, and Gungahlin. The first two are based on Walter Burley Griffin’s designs. The others, which are sympathetic extensions to Griffin’s inner city design, were added later as Canberra grew. All have a land contour design and a central shopping area known as a Town Centre. The districts are generally separated from each other by bushland reserves, many of which have wildlife such as kangaroos and kookaburras.

Initially almost all construction work in the Capital was undertaken by the Government. Government built homes, required to house the public servants transfered from Melbourne, were the basis of Canberra’s first suburbs. These suburbs, built slowly over the next several years, were Parkes, Barton, Kingston, Braddon and Reid. They initally often had other names – for instance, Kingston was originally known as Eastlakes – before a formal renaming procedure took place in 1928. They were built largely in accordance to Walter Burley Griffin’s designs for Canberra. The men who constructed these suburbs lived in a series of worker’s camps, which consisted of tents and some brick cottages, mainly in the area now known as Manuka.

The naming of the major streets in the inner city triangle as well as these first suburbs were a vital part of Griffin’s plan in which both the layout and the names of the suburbs and the roads that connected them were all deeply symbolic. The three points of the triangle were the City Centre, Capital Hill and what is now the roundabout at Russell. The City Centre, now more commonly known as City, was intended to be and still is the business hub of the Canberra. Capital Hill was to be the seat of National Government – Parliament House was built there in the 1980s – and Russell was to be the shopping area. Of the three axis points, the latter is the only one to not have been developed in accordance with the Griffin master plan.

The three axis points were symbolic of the British Government (City Centre), the Commonwealth of Australia (Capital Hill) and the people of Australia (Russell). The circuit at the axis of the City Centre was named London Circuit, after the seat of British Government, which the City Centre symbolised. Capital Hill and Capital Circuit at the locality were thus named as they signified the purpose behind the creation of Canberra – to be Australia’s new capital city with the Governmental function centralised there. The third axis point, at the intersection of Kings Avenue and Constitution Avenue, was to have a produce market at the centre of its circuit.

The three axis points were joined by three grand avenues – Constitution Avenue, which symbolised the link between the Australian people and the British Crown via the Australian Constitution; Commonwealth Avenue, which symbolised the Legal and Political connection between Gt Britain and Australia as the mother country and a member of its commonwealth; Federal Avenue (later changed to King Avenue), which symbolised the Federation of Australia that unified the people of the various states of Australia as a single nation via the Federal Government. The major Government buildings were placed – and remain today – within the boundries of those three axies in what became the suburb of Parkes, which was appropriately named after Sir Henry Parkes, a man whose vision of a unified federation of states coming under a single national Government was the catalyst behind the creation of the city of Canberra.

On Griffin’s master plan, a series of grand avenues radiated out from State Circle on the perimeter of Capital Hill – the centre of national Government – leadng to the major suburban areas of Canberra planned for the city’s south. These major arteries were named after the state and territory capitals – Brisbane Avenue, Sydney Avenue, Hobart Avenue, Melbourne Avenue, Adelaide Avenue, Perth Avenue and Darwin Avenue – their design and location being symbolic of the states and territories radiating out from State Circle and the unifying Federal Government seated at the heart of the national capital (Capital Hill), which is at the head of the city’s physical and symbolic triangle.

These radiating avenues were layed out in such a way as to point in the general direction of the cities after which they were named – Melbourne Avenue in fact points directly towards Melbourne. On the initial plan, each of the state capital city avenues would terminate with a park named after the generic botanical name for a native plant from that particular state; for example, Telopea Park is named after the waratah, the floral emblem of New South Wales, and is at the end of Sydney Avenue, which in turn is named after the capital of New South Wales.

The park at the end of Brisbane Avenue was eventually named after Sir George Ferguson Bowen (1821-1899), a Governor of Queensland; Perth Avenue’s park now honours Western Australia’s founding Lieit-Governor, Sir James Stirling; Hobart Avenue’s park is similarly named, honouring the founder of Hobart, Lieut. David Collins. Melbourne Avenue was to terminate at Latrobe Park (honouring the first Lieut-Governor of Victoria, Charles Latrobe) but ended up being called Canberra Nature Park. The park and circuit that were to be at the end of Adelaide Avenue (at the site of the bridge carrying Kent Street, Deakin over Adelaide Avenue) were never built.

All the state avenues were built in accordance to Griffin’s plan except for Perth Avenue and Darwin Avenue. Both of these avenues were to be in what became the suburb of Yarralumla. Griffin’s plan for this area was to be similar in design to Kingston – triangular in shape with Capital Hill. The Adelaide Avenue park and circuit and a park and circuit on the lake at Orana Bay were the triangle’s axis points. Adelaide Avenue, Perth Avenue and what became Novar Street line up with the perimeters of Griffin’s triangle.

A grand design that would have placed Yarralumla’s foreign embassies and high commissions in a magnificent setting, Griffin’s final plan of 1918 was abandoned totally, perhaps because the terrain of the area made the adoption of his design impractical without major earthworks. A consequence of scrapping Griffin’s plan for the suburb that became Yarralumla is that Darwin Avenue (which was to have left State Circle where Rhodes Place is today) was never built in its intended position. Today, Darwin Avenue looks somewhat of an after-thought, being a dead end street off Perth Avenue. It main saving grace is that it points in the direction of Darwin. Perth Avenue leaves State Circle where planned, but deviates immediately to the north of its original position, allowing it to follow the terrain. It radiates towards the city of Perth as it did on the Griffin masterplan, but is lest than half its originally intended length.

Thrown into Griffin’s original mix of state avenues radiating from State Circle was Wellington Avenue which was to terminate at Manuka Park. Readers with a knowledge of New Zealand geography will recognise Wellington as being the name of New Zealand’s capital city and Manuka as being the common name of the New Zealand tea tree Leptospermum scoparium. When Griffin drew up his plans in 1912, there was much optimism that New Zealand might join the Federation of Australia, and New Zealand was included in the eight avenues radiating out from Capital Hill both as an incentive to join and to make New Zealand feel welcome if they accepted the invitation to become Australia’s seventh state. Before the name Wellington Avenue was gazetted it was realised that New Zealand was not going to become part of a Confederation of Australasia and the name was changed Canberra Avenue. Manuka, now the name of the locality at the end of Canberra Avenue, was left unchanged.

The area around Manuka Park, which was at the point where the suburbs of Forrest, Griffith and Kingston met, was already known as Manuka, though it does not officially exist as a suburb. The name had come into common use very early as it was around Manuka Park that the majority of homes to house the builders of early Canberra were built. Ironically, the most well known suburb of Canberra today is not only not a suburb, but its recalls a union within the federation of Australian states and territories that was never forged.

Braddon, Reid and Ainslie (established 1928), all part of Griffin’s North Canberra, were also among the earliest suburbs to be built, and were, in the main, laid out true to Griffin’s street plans for these areas. Of all of Canberra’s residential suburbs, they remain truest today to Griffin’s master plan. The sections of Acton, Turner and O’Connor which are closest to Northbourne Avenue (established 1928) were also built to Griffin’s street plans, but the eastern sections of these suburbs (developed post-World War II), particularly Acton and O’Connor, have departed totally from them. Acton’s departure no doubt came as a result of the siting of Australian National University within its perimeter. Turner was the last pre-World War II suburb developed to the garden city concept with super-wide nature strips. In fact it is said that Turner represents the pinnacle of spacious garden city design with wide 12 metre nature strips and generously wide roads that give a more spacious feel than older suburbs such as Reid and Braddon, and more consistently wide nature strips and larger parks than Canberra’s slightly later post-World War II suburbs like O’Connor.

The name of the main road through Canberra’s northern suburbs, Northbourne Avenue, appears on the original plan by Griffin. It comes from the combination of two words, ‘North’ and ‘Bourne’. North because the road is on the north side of Canberra; Bourne comes from an old French word meaning limit or boundary, destination or goal. Hence, Northbourne means the northern edge or limit of the town, or the northern destination in this part of the town.

The early suburbs of Canberra, which are contained in all the districts detailed above, are mainly named after famous Australians. Some are named after early settlers or Aboriginal terms. Street names within each suburb – and subsequent suburbs created – generally follow a particular theme. For instance, the streets of Duffy are named after Australian dams and weirs, Page’s streets are named after biologists and naturalists, and the streets of Gowrie are named after Australian Victoria Cross recipients.