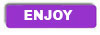

Though Uluru is the largest “free-standing” monolith, Mount Augustus is the world’s largest monolith. Located 320 km east of Carnarvon in Western Australia, it is 2.5 times larger than Uluru (Ayers Rock). One of the most spectacular solitary peaks in the world, standing at 1105 metres above sea level, Its summit has a small peak on a plateau, and rises about 717 metres above a stony, red sandplain of arid shrubland dominated by wattles, cassias and eremophilas. The rock is 8 km long and covers an area of 4795 hectares. Because of its immense size, the mountain is clearly visible from the air for more than 160 kilometres. It is made of sedimentary rocks, Upper Proterozoic sandstone and conglomerate which, according to geologists, was originally deposited on an ancient sea floor about 1 000 million years ago, then later folded and uplifted. The rock has a variety of colours, ranging from purple, to pink, orange and red.

Mount Augustus is named after explorer Sir Augustus Charles Gregory (1819-1905). It was named by his brother Francis Gregory on 3rd June 1858, during his epic 107 day journey through the Gascoyne, when he became the first European to climb the mountain. Aboriginal etchings can be found on Mount Augustus, whivh is known as Burringurrah in the local Aboriginal language. There is a hiking trail to the top of Mount Augustus.

- More

- More

- More

- More

- More

- More

- More

- More

Uluru is one of Australia’s most famous landmarks and is the country’s most visited site. The mysterious red monolith is the weathered peak of a buried mountain range and rises some 430 metres from the desert and has a perimeter of 9.4 km. It rises 345 metres above the plains, and is believed to extend several kilometres below the surface and covers an area of 3.3 square kilometres. The red colour of Uluru is due to iron minerals in the surface rocks oxidising with the air.

As you approach Ayres Rock it can appear to change colour, the sandstone taking on various hues of red, purple, orange, grey and yellow, depending on weather conditions and your distance from it. Ayres Rock has officially been known as Uluru since it was returned to the Anangu, the Aboriginal owners, in 1985. It was then leased to the Australian government and is now jointly administered. Ayres Rock Resort was developed at Yulara in the early 1980s to cater for visitors and is designed to blend in with the environment. The Rock is 450 km (270 miles) west of Alice Springs in the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park which covers over 132 000 ha.

The third of the great monoliths, Mount Conner is 100 kilometers east of Uluru and on the western fringe of the vast Northern Territory cattle station, Curtin Springs. Called Atilla by the Aboriginals, it looks a bit like Uluru, however it is in fact lower and wider. Circling Mount Connor reveals a series of rugged gorges, a perfect haven for small populations of Red Kangaroos and Rock Wallabies. Because of the dams built for watering cattle, wildlife is more prevalent in this part of the desert. Like Uluru, Mount Conner dramatically changes colour throughout the day as the sun changes its position above. Surrounding Mount Conner are vast salt lakes that scientists believe are remnants of ancient inland oceans, complete with fossilized remains.

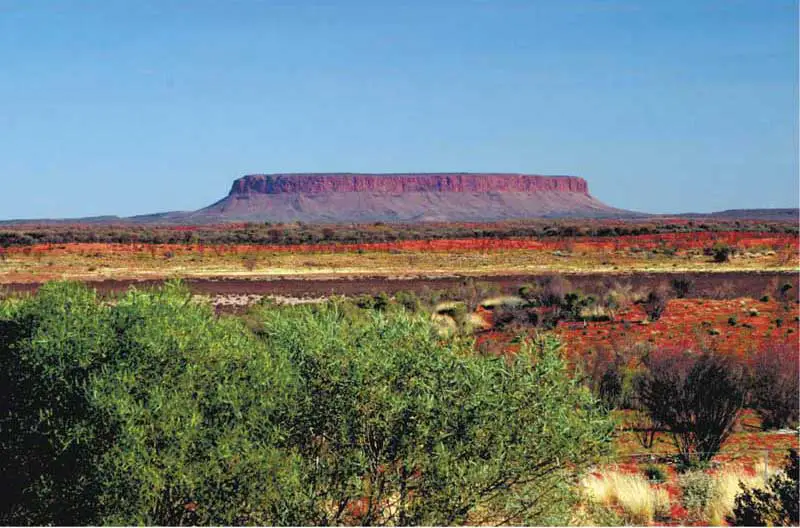

Located near the Western Australian wheatbelt town of Bruce rock, Koberin Rock is the third largest free standing monolith in Australia and is recognised as an interesting unspoilt spot for flora and fauna study. The granite rock covers 9 hectares and towers 122m above ground level. The rock features interesting formations, caves and a deep well on the western side. Up close it gives the appearance of being a smaller version of Hyden’s Wave Rock as it also has a “wave” wall. The rock is an unspoilt area and visitors can spend hours exploring the Devil’s Marbles, Dog Rock, Wave Wall, scenic lookouts, cave and historical sites. Kokerbin Rock, also known as Kokerbin Hill, is situated approximately 40 km north west of Bruce Rock on the Bruce Rock-York Road.

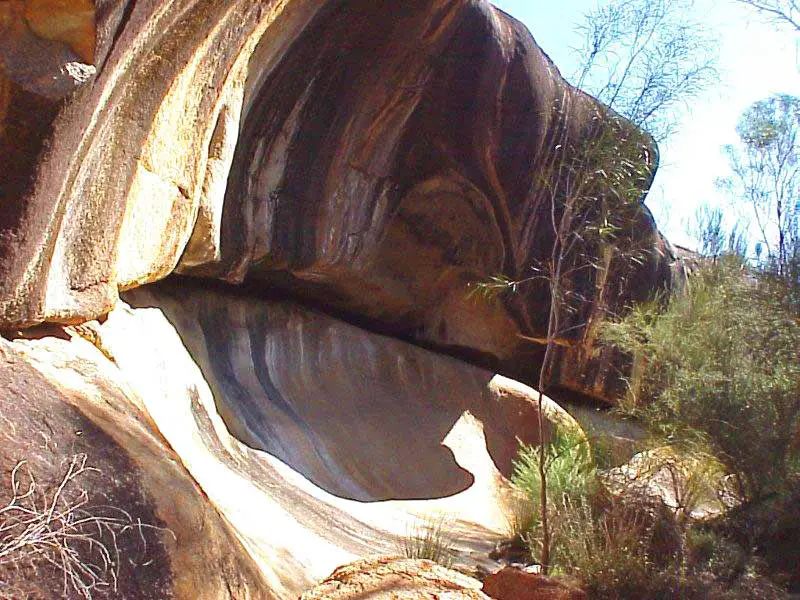

Situated in Bald Rock National Park on the New South Wales-Queensland border, Bald Rock is Australia’s largest granite monolith, and rises to 1277 metres above sea level. It towers about 200 metres above of the surrounding bushland, is 750 metres long and 500 metres wide. The granite dome is actually water streaked, creating a striking view on any day.

Bald Rock National Park is tucked away in the thickly timbered country between Stanthorpe and Tenterfield along the Queensland-New South Wales border, accessable to conventional vehicles from the Mt Lindsay Highway. The park has two distinct walking tracks, both leading to the top of the rock. These tracks are clearly marked. From the top visitors are rewarded by expansive views across a beautiful granite outcrop dotted landscape. Around the base of the rock are stands of eucalypts, mainly stringy-bark and New England blackbutt. The park has a small camping area for those wishing to extend their stay and is just 39km from Stanthorpe.

Mt Wudinna, SA’s largest exposed monolith, is located approximately 12kms northeast of Wudinna in South Australia’s granite country. In addition to its fascinating geological landforms, Mount Wudinna, like many of the bare granite hills in the district, is encompassed by low stone walls to catch and divert run off water. These channels were constructed by hand when the area was first settled and provided the only source of water for farms and the town for a number of years. Mount Wudinna stands 260 m above the surrounding area and covers an area of about 112 ha. Mount Wudinna, which is by far the largest of the region’s granite outcrops, was first sighted by Europeans in 1844 when the explorer John Charles Darke passed through the area looking for good pastoral lands. He was fatally speared a short time later by Aborigines at Waddikee, between the present day sites of Kyancutta and Kimba.

Situated 48 kilometres west of Cue via Austin Downs Station, this huge granite monolith is 50 metres high, 1.5 kms long and 5 kms around. A large cave contains an impressive gallery of Aboriginal paintings, making the site of deep cultural and spiritual significance to the Aborigines. Most probably painted with ochre from Wilgie Mia, the gallery features “motifs that are predominantly non-figurative, with concentric circles, spirals, single and multiple wavy lines, arcs and U-shaped outlines. The figurative art includes anthropomorphic shapes, bird and animal tracks and stencils of hands and implements. A number of hands with up to seven fingers have also been drawn. A number of the paintings are so high above the present ground level that some form of scaffolding must have been used by the artists who produced them.

One of the more outstanding is that of a ship with two masts, ratlines, rigging and square portholes in the hull, a remarkable occurance considering the site is over 300 kilometres from the sea. It is believed to depict on of the Dutch ships that visited the region’s shores in the 17th century. Legend has it that one of the two sailors cast ashore at Kalbarri by the Commander Pelsart of the ‘Batavia’ which was wrecked on the Abrolhos Islands in 1629, painted the figure of the sailing ship on the rock. Alternatively it has been suggested it depicts the Zuytdorp, wrecks on the coastline north of Kalbarri in 1711, or perhaps a pearling lugger. Anthropologist Dr Ian Crawford, author of the book, Art of the Wandjina, has raised the possibility that the Walga Rock painting may not be a representation of either the Zuytdorp (1711) or a pearling lugger, as once thought. He was struck by the possibilities that it represents the Xantho. There appears to be some strength to his proposal. The painting is clearly visible.

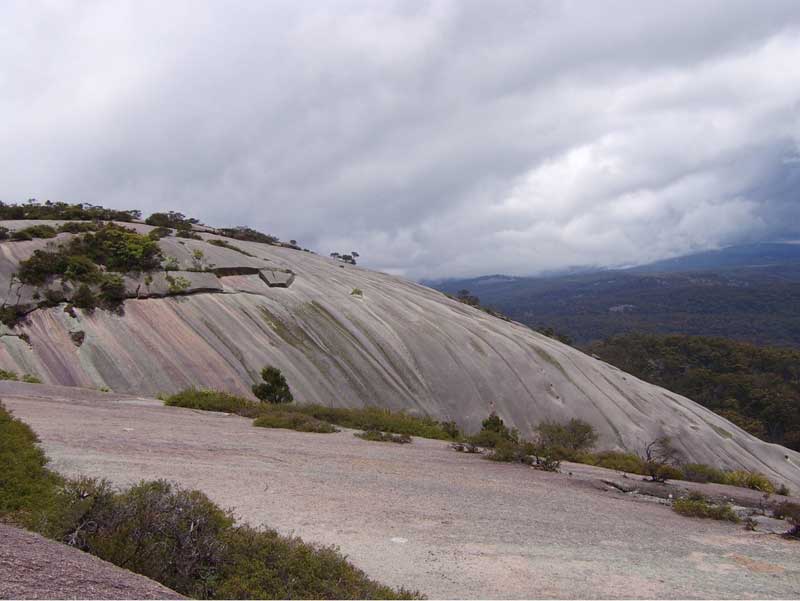

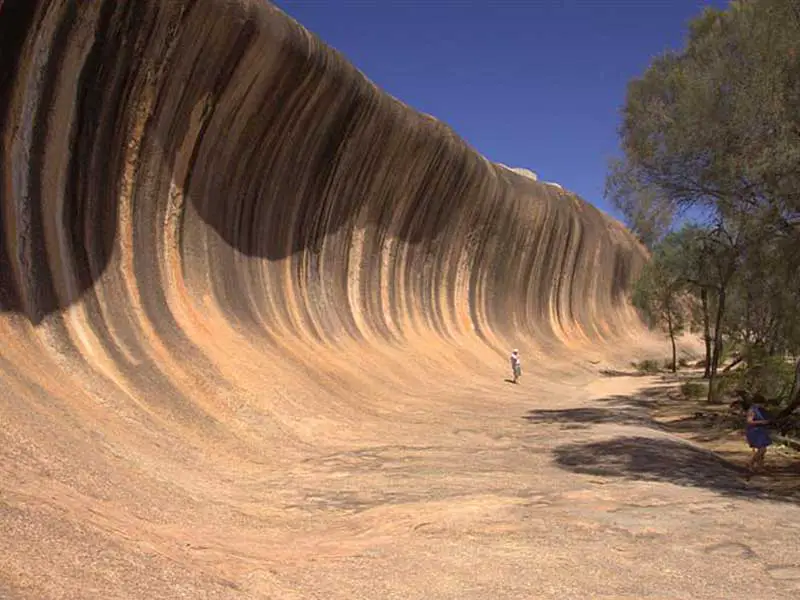

14 metres high, and 110m long, the face of Wave Rock appears ready to crash onto a pre-historic surf, now frozen in time. Believed to have formed over 2700 million years ago, Wave Rock is part of the northern face of Hyden Rock. The shape of the wave is formed by gradual erosion of the softer rock beneath the upper edge, over many centuries. There are actually several examples of granite “waves” in the Hyden area.

The colours of the Wave are caused by the rain washing chemical deposits (carbonates and iron hydroxide) down the face, forming vertical stripes of greys reds and yellows. If you can stay a little longer, it is also worth seeing the Rock at different times of the day, as the changing sunlight alters its colours and appearance. In addition to being an impressive tourist attraction, the rock has been converted in to a catchment for the town’s water supplies, with a foot-high concrete wall around the upper edge of Hyden Rock directing rainfall into a storage dam.

Located near Mt Wudinna, Pildappa Rock is a unique pink inselberg located 15 kilometres northeast of Minnipa. Situated in South Australia’s granite country, it is proudly proclaimed by locals as a rival to the more famous “Wave Rock” located in Hyden WA. Formed about 1500 million years ago Pildappa Rock is part of the vast Gawler Craton – a geological shield structure covering central Eyre Peninsula, the Gawler Ranges and large parts of outback South Australia. Geologists refer to Pildappa Rock and other inselbergs in the area as belonging to the Hiltaba suite of rocks – basically orthoclase rich pink granites dating from Eyre Peninsula’s Precambrian age.

Nearby the Gawler Ranges were formed as a result of volcanic action. Unlike the Gawler Ranges however, Eyre Peninsula’s inselbergs were formed as Batholiths or granite domes some 7 kilometres below the earth’s surface. Clearly much soil erosion has occurred during the past 1500 million years. Equally remarkably, Pildappa Rock and many other Australian inselbergs exhibit very slow rates of weathering – with numerous studies indicating exposed granite surfaces eroding at rates below 50 centimetres per million years.