Now and then: British Shipbuilding

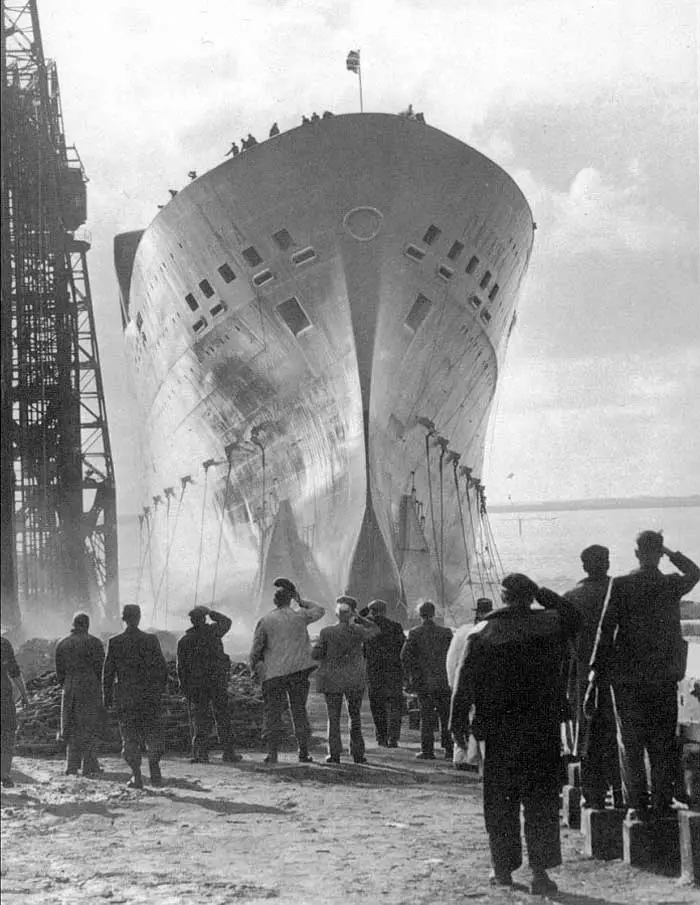

SS Oriana was launched on the 3rd November, 1959 by Princess Alexandria of Kent. Yard No 1061, Vickers-Armstrong (Shipbuilders) Ltd, Barrow-In-Furness.

In 2016, the British Government announced a lucrative deal to build new fuel ships for the Royal Navy that will support thousands of jobs. But the order for four of these ships has not been placed with Britain’s remaining shipyards. Instead the Government awarded the contract to shipbuilder Daewoo which operates massive shipyards across South Korea. The order was just a drop in the ocean for the Asian country, which before the 1950s had no maritime pedigree to speak of. At the time the order was placed South Korea has 774 commercial vessels on order. The only commercial ship in Britain being built was a small Scottish island ferry. So what happened to the once mighty and world beating British shipbuilding industry?

The rise of the jet-powered airliner in the late 1950s sent the demand for ocean liners into decline. Around that time, the industry was exposed to competition from newly developed low-cost Asian yards. First Japan jumped aboard, using the building of ships to shore up its economy that had been shattered during the war. South Korea followed and by the 1970s the two nations were building the lion’s share of the world’s merchant fleet. Now it is the unstoppable economic machine that is China that builds the most. They have more than 2,000 ships on their books, with many firms destined to ship their products to Europe, America and Australia, while others importing vast amounts of raw materials from Africa and South America.

What Happened to British Shipbuilding?

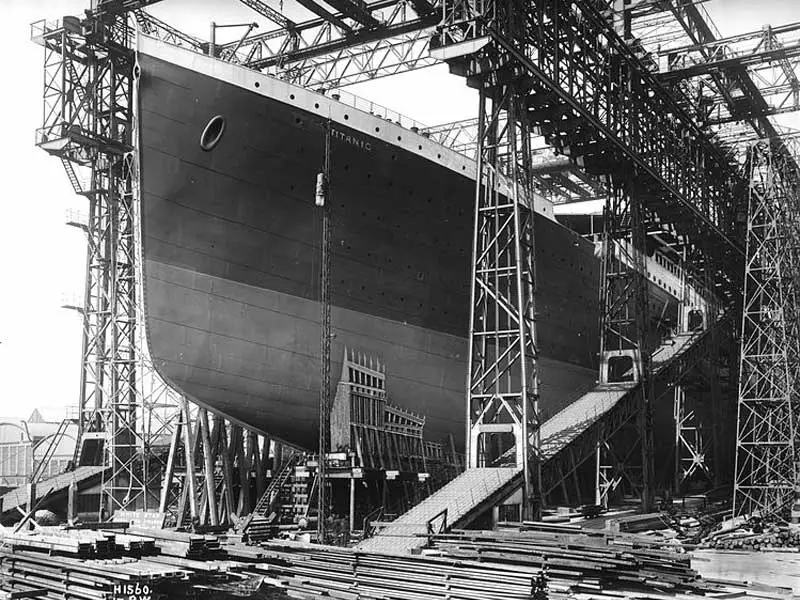

While the industry has largely decamped to Asia, Britain’s European neighbours still build ships. Some 53 ships are in the pipeline in Norway, with the majority of them specialist ships to service the North Sea oil industry, which, of course, it shares with Britain. The giant luxury cruise ships gracing Southampton docks are all mostly built in European shipyards. Currently 28 are on order. Cunard had wanted to build the Queen Mary 2 in a British shipyard. The only one able to was Belfast’s Harland and Wolff, which built the iconic ships such as Titanic and Canberra. But the Government failed to provide the guarantees necessary to build it and so the order went instead to French shipbuilders Chantiers De L xAtlantique in Saint-Nazaire.

RMS Titanic under construction, Belfast, 1911

Along with France, Germany’s workforce has benefited from building passenger vessels. And unlike Britain these countries and others have also successfully exported warships. Dr Duncan Redford, senior research fellow at the National Museum of the Royal Navy, said: “Fundamentally warship building in the UK for many years has solely been about supporting the Royal Navy, but others have not just supported their own indigenous requirements but made a virtue of exporting its shipbuilding designs.”

Spain has completed two 27,000 tonne Canberra Class Amphibious Assault Ship (LHD) for Australia, once big customers of British shipyards. The announced closure of BAE’s shipbuilding operations in Portsmouth in 2016 ended more than 500 years of shipbuilding in Hampshire which included the construction of Admiral Lord Nelson’s warships at Buckle’s Hard in the New Forest and 100 years of shipbuilding in Woolston, Southampton, by the company latterly known as Vosper Thornycroft. It also signified another chapter in the decline in British sea power. A century ago Britannia really did rule the waves with two-thirds of the world’s ships flying the red duster.

University of Southampton historian John McAleer, a former curator at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, said: “I think that is what is niggling people as well as the obvious worries about jobs and industry. Britain’s maritime heritage is Britain’s history. The two are absolutely interlinked.”

So what went wrong for this once mighty industry? The reality is that British shipbuilding has been in trouble since after the Second World War.

Some say it was industrial strife between management and unions. Others blame lack of investment in new equipment and cost effective manufacturing techniques. But the general consensus is that Britain’s ships were too expensive and that huge new shipyards in the emerging economies of Japan and South Korea, were simply producing cheaper ships by the 1970s.

SS Strathmore under construction, 1935

The crunch for commercial British shipbuilding came in the 1980s with a double whammy of world recession and a strong pound making Britain’s ships too expensive. The battle between disruptive unionisism and Margaret Thatcher’s Tory Government didn’t help. The labour party was determined to cripple the profits of business by any means and their method was to disrupt every possible enterprise involving mass labour through disruptive unionisation. The Thatcher Government was equally determined to crush the power of the unions, and their battle resulted in the destruction of the marine industry among others. Mass labour businesses nearly all vanished, shipbuilding among them. Anybody wanting to run anything involving thousands of people even today is still faced with the hostility of unions who appear to have learnt nothing.

The final nail in the offin of ship building and repairing in the UK was the stopped of the subsidy of the ship building industry by the Thatcher government (this subsidy also gave the right for government to use those ships in times of war). Other countries that build ships still give there shipbuilding industry subsidies, which gives them the legal right to call on the ships use if they are in a war. Ironiclly, the UK is a world leader in ship design and technology, its new RFA ships were designed there. Cunard’s Quen Mary 2 was designed there and is packed with British technology and craftsmanship.

But leading shipbuilding expert Dr Martin Stopford, who worked in the industry for decades, says the opportunity for Britain to build ships again has probably gone forever: “The price we could sell a bulk carrier for would just buy the materials to build it.” While strict European Union subsidy rules for shipbuilding were observed in the UK, he says other countries were less transparent than Britain and a little cleverer at funnelling subsidies into their yards. Meanwhile he said countries such as Germany, France and Italy had made a strategic decision to build cruise ships which is something their Asian counterparts were unable to do.

“As the cruise ship industry boomed they (the European shipyards) could supply the vessels, while Britain’s yards had missed the boat. After shipbuilding in Portsmouth stops next year, just two BAE systems shipyards in Glasgow and one submarine builder in Barrow in Furness will be holding the flame of a once mighty industry. They will continue to build cutting-edge warships into the next decade but represent a tiny fraction of what once was. The irony for British shipbuilding is that while Britain’s industry has fallen behind, we are entering a golden age of shipping with tens of thousands of vast container ships criss-crossing the globe carrying goods between continents.”

Shipyards: Clydebank (Glasgow)

The giant Titan crane, the sister to the one then once stood at Sydney’s Garden Island Naval Base, is one of the few relics remaing from the giant John Brown ship building facility than once stood on the banks of the Cyde at Glasgow, Scotland. The crane was used to place the engines in many iconic ocean liners built at the John Brown shipyards, including the Queen Mary, the original Queen Elizabeth, the Lusitania, HMS Hood and HMS Repulse. The last of these great ships to be built here was the Queen Elizabeth 2 (QE2). At its height, from 1900 to the 1950s, it was one of the most highly regarded, and internationally famous, shipbuilding companies in the world. Today, the Titan crane is used for bungie jumping.

SS Queen Elizabeth 2, September 1967

The Clydebank Titan crane today

Shipyards: Barrow-in-Furness

Barrow-in-Furness is an insustrial town on England’s Cumbian coast to the south west of the Lake District. It was here that the ship RMS Strathaird, the P&O; liner on which my family and I migrated to Australia in May 1960. I have fond memories of the trip, which had kindled his life-long interest in ships and things maritime-related, so to visit the place where it all started had always been a goal of his.

As with other similar localities around the UK, the shipyards are long gone but museums recall the days when shipbuilding provided work for thousands of people in ports around the British Isles. Here at Barrow-In-Furness, the Dock Museum keeps the memory of those days alive. Familiar names of many ships that brought migrants to Australia – Orion, Orsova, Oriana, Himalaya, Chusan, and of course the four Strath sisters – all are honoured at the place where they were built and launched.

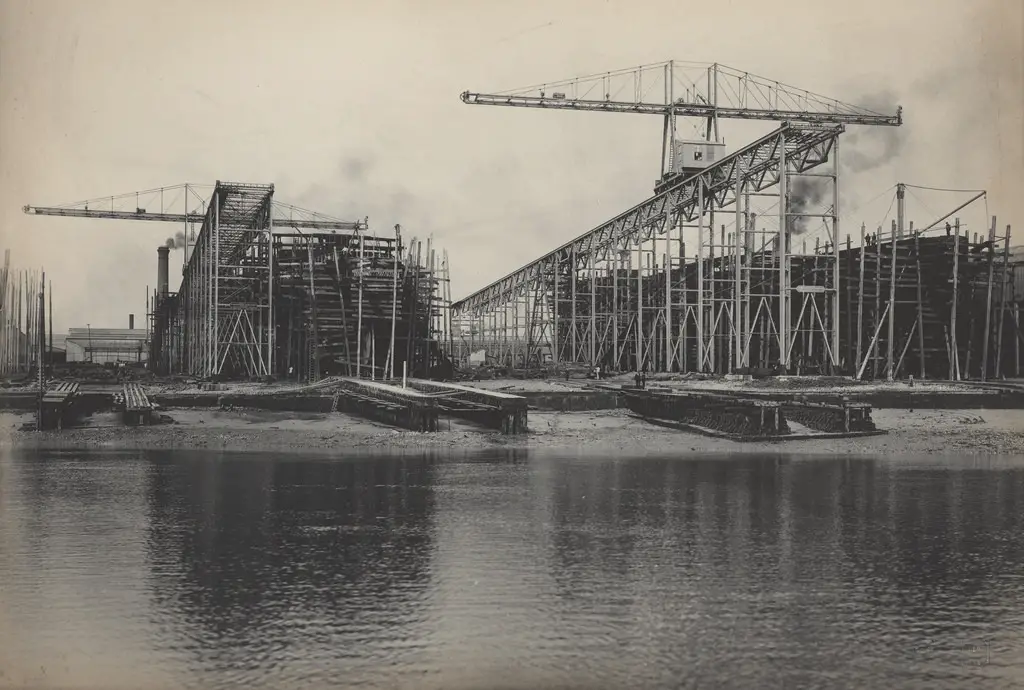

Barrow slipways

The same site today

Shipyards: Wearside (Sunderland)

Sunderland was once the biggest shipbuilding town in the world. Now the banks of the River Wear stand empty and silent. It all started back in 1346, when Thomas Menvill had a shipbuilding yard in Hendon. Throughout its history Sunderland has had over 400 registered shipyards. Between 1846-64, Wearside ship builders produced almost one third of all ships ever made in Britain. The 1850s were the best years, with 1,536 ships being built during the decade.

The world-famous Liberty Ship was among the designs to be created, produced and manufactured at the Thompson and Son’s yard’s at North Sands. Liberty ships, a type of mass-produced cargo ships built to inexpensively meet the United States’ World War II maritime transport needs. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s many yards closed or merged. In 1977 the shipbuilding industry was nationalised and job losses followed. In 1980 the last two remaining yards merged, then only eight years later on the 7 December 1988 this last remaining yard on the Wear closed bringing shipbuilding in Sunderland to a sad closure. Where Sunderland University’s St Peters Campus and The National Glass Centre now stand on the River Wear, was where the site of the last ship building yard.

Launch of ‘Sir Archibald Page’, 1950

The same site today

Shipyards: Wallsend, Tyneside (Newcastle)

Wallsend, historically Wallsend on Tyne, is an area in North Tyneside. Historically part of Northumberland, Wallsend derives its name as the location of the end of Hadrian’s Wall. Wallsend has a history of shipbuilding and was the home of the Wigham Richardson shipyard, which later amalgamated to form Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson, probably best known for building the RMS Mauretania. This express liner held the Blue Riband, for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic, for 22 years.

Other famous ships included the RMS Carpathia which rescued the survivors from the Titanic in 1912, and the icebreaker Krasin (launched as Sviatogor) which rescued the Umberto Nobile expedition on Spitzbergen in 1928, when Roald Amundsen perished. The story is retold in the movie The Red Tent, starring Sean Connery and Peter Finch. WWII ships built here include HMS Sheffield and HMS Victorious which took part in the sinking of the Bismarck. Other ships built there include the new HMS Ark Royal in the 1980s. The shipyard closed in 2007. The former Wallsend Slipway & Engineering Company Shipyard continues to operate, constructing offshore oil rigs and as a TV studio, productions from there include the hit ITV drama Vera starring Brenda Blethyn and Inspector George Gently starring Martin Shaw.

HMAS Sydney takes to the water for the first time, 22 September 1934

The same location today

Shipyards: Harland & Wolff (Belfast)

Harland & Wolff is most famous for having built all of the ships intended for the White Star Line including RMS Titanic. Other well known ships built by Harland & Wolff include Titanic’s sister ships RMS Olympic and RMS Britannic, the Royal Navy’s HMS Belfast, Royal Mail Line’s Andes, Shaw Savill’s Southern Cross, Union-Castle’s RMS Pendennis Castle, and P&O;’s Canberra. Harland & Wolff was formed in 1861 by Edward James Harland (1831-95) and Hamburg-born Gustav Wilhelm Wolff (1834-1913). In 1858 Harland, then general manager, bought the small shipyard on Queen’s Island from his employer Robert Hickson.

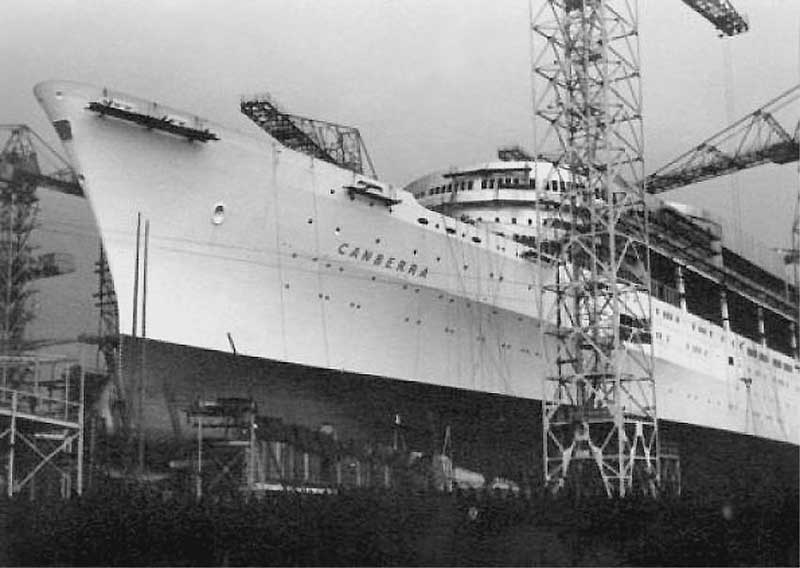

P&O; liner SS Canberra under construction, October 1959

In 1912, the three neighbouring yards were amalgamated and redeveloped to provide a total of seven building berths, a fitting-out basin and extensive workshops. It was during this period that the company built Olympic and her sister ships Titanic and Britannic between 1909 and 1914, commissioning the construction of a massive twin gantry and slipway structure for the project. In the First World War, Harland and Wolff built monitors and cruisers, including the 15-inch gun armed “large light cruiser” HMS Glorious. The shipyard was busy in the Second World War, building six aircraft carriers, two cruisers (including HMS Belfast) and 131 other naval ships; and repairing over 22,000 vessels. It also manufactured tanks and artillery components. It was in this period that the company’s workforce peaked at around 35,000 people.

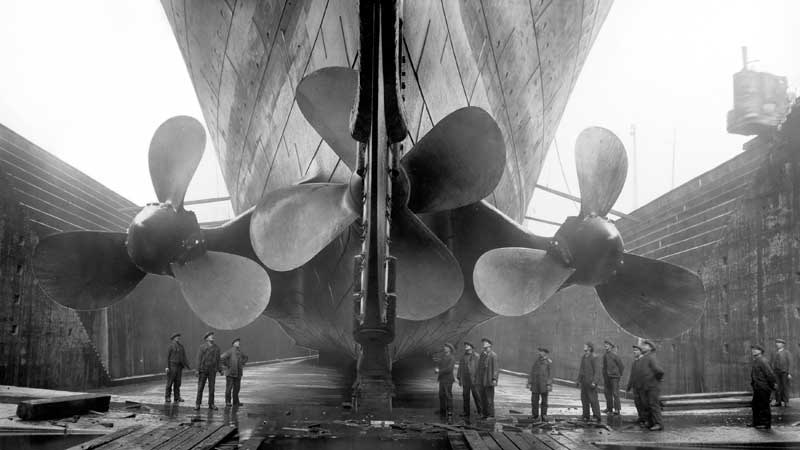

RMS Titanic’s Propellers, 1911

Thompson Graving Dock, Belfast. When built in 1911 for RMS Titanic, it was the largest dry dock in the world.

The last liner launched by the company was MV Arlanza for Royal Mail Line in 1960, whilst the last liner completed was SS Canberra for P&O; in 1961. The company was bought from the British government in 1989 in a management/employee buy-out in partnership with a Norwegian shipping magnate. By this time, the number of people employed by the company had fallen to around 3,000. The company bid unsuccessfully tendered against Chantiers de l’Atlantique for the construction of Cunard line’s new Queen Mary 2 in 2001.

Turbines for the Ormonde Offshore Windfarm being assembled at Harland & Wolff, Belfast.