Cook's landing at Botany Bay

Of all the names that appear on the list of greats in the history of Australian exploration, none has been more glamourised than James Cook. As a result of him being given almost Godlike status by historians, governments, teachers and students, the majority of Australians actually believe Captain Cook discovered Australia. They of course are wrong on two counts. For a start, when he made his voyage of discovery to Australia, his rank was Lieutenant, not Captain, and then there is the evidence that indicates his discoveries may well have been re-discoveries, made some 200 years after the first visit.

That doesn't mean he didn't play a significant role in Australian history. On the contrary, his surveys and charts were the first detailed, accurate account of what the Australian continent was like, not only in the shape of its coastline, but its mountains, rivers, beaches and bays, its flora, fauna and its inhabitants to the extent it is possible to observe by exploring a ribbon of coastline. As a result of Cook's exploits, Terra Australis Incognita had become Terra Australis, no longer an unknown quantity, Cook quite put literally put Australia on the map. For this he will and should be eternally remembered.

James Cook was born in the village of Marton, Yorkshire on October 27, 1728; he was one of seven children born to a day laborer. Cook received basic schooling at the village school and was then sent to work for William Sanders in the nearby fishing village of Staithes. Here he developed a love and fascination for the sea, but he was not especially happy with his job amongst the hard working people of the land. In July 1746, at the age of 17, Cook gave into his temptations for the sea and became an apprentice to the Walker Family, ship owners, at the port of Whitby. A bustling port, Whitby was always filled with many varieties of ships. Cook's job as an apprentice required him to become very familiar with the coal ships of the area and he soon learned the ins and outs of the colliers type ships. He worked hard and soon had his first voyage aboard the Whitby collier 'Freelove.'

James Cook was born in the village of Marton, Yorkshire on October 27, 1728; he was one of seven children born to a day laborer. Cook received basic schooling at the village school and was then sent to work for William Sanders in the nearby fishing village of Staithes. Here he developed a love and fascination for the sea, but he was not especially happy with his job amongst the hard working people of the land. In July 1746, at the age of 17, Cook gave into his temptations for the sea and became an apprentice to the Walker Family, ship owners, at the port of Whitby. A bustling port, Whitby was always filled with many varieties of ships. Cook's job as an apprentice required him to become very familiar with the coal ships of the area and he soon learned the ins and outs of the colliers type ships. He worked hard and soon had his first voyage aboard the Whitby collier 'Freelove.'While Cook was at Whitby, he educated himself a great deal in navigation and mathematics. By 1755, after nine years, and much service as ship's master, Cook left his ship and enlisted in the Royal Navy as an ordinary sailor. He boarded the Eagle, a 60-gun ship, and was sent to the North American Coast. Cook worked his way up through the ranks quickly in the navy, eventually rising high enough to command his own survey vessel. This was unusual for an enlisted man, but his experience at Whitby helped him have an upper hand over the other seamen. Cook's first mission was to map the estuary of the St. Lawrence River before Wolfe's naval assault on Quebec. Later he surveyed the coast of Newfoundland. Cook's stellar work with mapping and surveying was noted and how extremely accurate his drawings were. It was those surveys that gave Cook a name, along with information he carefully obtained from the observing and recording of the eclipse of the sun in 1766. Cook was rewarded for his work in Quebec in 1761; he received a bonus of 50 pounds, for "indefatigable industry in making himself the 'master of the pilotage.'" The surveys were so accurate and complete that they were in use until the beginning of the Twentieth Century.

Cook returned to England in 1762 and soon married Elizabeth Batts of Shadwell, the only daughter of a provincial family. In Elizabeth's seventeen years of marriage to Cook she saw him only every few years and even then only for a few months at a time. His surveys and scientific observations, along with his own scientific ability and the patronage from his former commander, Sir Hugh Palliser, led to his new position as Captain of the "The Endeavour Bark" in 1768.

In 1768 he was promoted and sent to the Pacific with an astronomical observation group where he surveyed Tahiti, New Zealand, and Australia. On his second expedition (1772-75) he explored Antarctica. In 1776 he undertook his third and final voyage in which he explored the West coast of North America and tried to locate a passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. On this voyage in the ships Resolution and Discovery he discovered the Hawaiian Islands (which he named the Sandwich Islands), and sailed up the coast of North America through the Bering Straits to the Arctic Ocean. He concluded that a usable passage to the Atlantic Ocean did not exist. On his return to Hawaii, he was killed by islanders in 1779. The voyage was completed without him in 1780. One of the senior officers who made the voyage home was William Bligh, who was later to be involved in the infamous mutiny on the Bounty, as well as the Rum Rebellion in Sydney during his term of office as Governor of New South Wales.

In addition to the Admiralty's official instructions to Cook regarding the Endeavour's first voyage of 1768-71, to the South Pacific, an additional "secret" set of instructions (click to read full text) were given to Cook, which outlined his instructions to search for the southland once the observation of the transit of Venus had been completed.

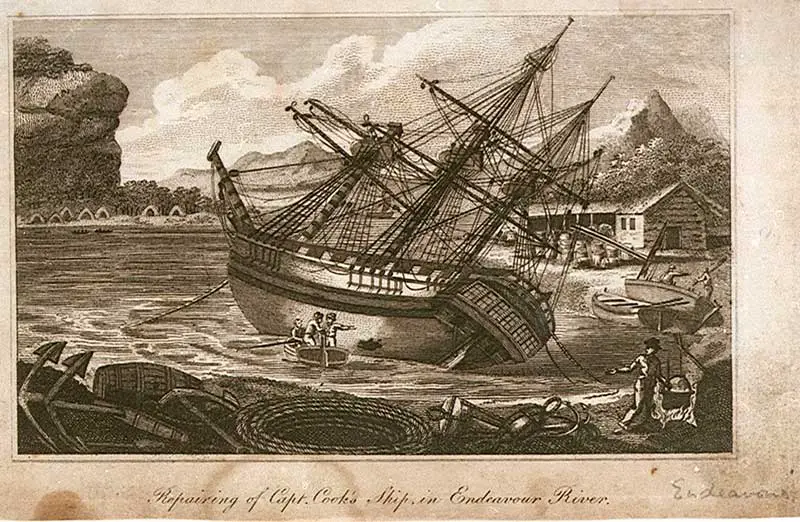

Replica of HMS Endeavour in its home town of Whitby, England

The ship chosen for Cook's expedition was the Endeavor Bark, a former Whitby-built east coast collier that had been refitted for the expedition. Although only 32 metres long and measuring 3 metres at her greatest width, the former Earl of Pembroke was roomy, sturdy and broad-bottomed and proved to be well able to withstand the rigors of the voyage. Besides, Cook would have been very familiar with that type of vessel, which was in common useage in the area where he grew up. There is every chance that he may have already been familiar with it.

On board was the accomplished botanist, Joseph Banks (below), who scored his berth and got to hand pick the scientists who were to travel with him by offering £10,000 to equip the scientific party. Among those chosen by Banks were Charles Green, an assistant at the Greenwich Observatory; eminent Swedish scientist Dr Daniel Solander, one-time pupil of the great botanist Carl Linnaeus; Swedish naturalist Herman Sporing; two natural history artists, Alexander Buchan and Sydney Parkinson; and four personal servants. His two greyhounds also joined the livestock aboard, which included a goat that had already circumnavigated the globe with Samuel Wallis, also aboard the Endeavour, who had commanded the frigate Dolphin on an expedition of discovery to Tahiti in 1766-67.

The Endeavour sailed from Plymouth Steps - the same steps from which the pilgrim fathers left aboard the Mayflower (left) - on 26 August 1768. Cook headed for the Strait of Le Maire, then passed Cape Horn and into the Pacific on 27 January 1769. After refreshing at several islands along the way, Cook anchored at Tahiti on 13 April 1769. In the log, he noted no ocean currents indicative of a nearby land mass and recorded he had no reason to believe a great land mass (Terra Australis) existed in the region. Cook's notes and journal about Tahiti began to identify him as great not only in navigation and the ways of the sea, but also as an observer of human ceremony, society, and culture. He lingered longer than any other European in this location, spending three months to build a fort at Point Venus from which to observe the transit. He circumnavigated Tahiti, and after the observation sailed for the other islands in the group, calling them the Society Islands (excepting Tahiti) because of their close proximity to each other, and taking possession for the Crown. Cook took on board a native priest, who was called Tupaia and his boy servant. Tupaia was an able navigator through regions of the Society Islands and proved to be a great asset in meeting peoples in New Zealand. The expedition left Tahiti on 9 August 1769.

True to the objective of discovery, following his Tahiti departure, Cook was set to resolve the issue of a great southern continent. As instructed, he sailed south to 40 degrees latitude at or by which point the proponents of the southern continent theory had said he would make landfall. On finding no land mass, Cook sailed west and into the eastern side of the land recorded by Tasman. At 40 degrees South latitude, Cook again recorded he had found no land. Furthermore, the nature of the ocean swell indicated no major land mass in the vicinity. The weather worsened and Cook turned northward and continued west. On 7 October 1769 land on the eastern side of New Zealand's North Island was sighted.

Cook plotted the coastline that Tasman had barely touched, surmising it could be an extension of the polar land Le Maire had identified as he (Le Maire) transmitted the southern end of South America. Le Maire called this Staaten Land, and Tasman conjectured with the same name. Cook intended to determine the relationship of Tasman's Staaten Land with the Staaten Land of Le Maire. He came to anchor in a bay he was to name Poverty Bay where he had his first encounter with New Zealand's Maoris. The Tahitian priest Tupaia was able to converse with the Maori natives, but he determined they were not friendly.

It was evident to Cook that the land continued to the south and as the winter weather had not yet abated, he decided to go north before exploring south. The next few weeks were spent charting the North Island. On Friday, 9th February 1770, after satisfying himself that it was an island, he turned south and set about discovering the southern geography. By mid March, after extensive exploration of the South Island, Cook began preparations for his departure of New Zealand. As far as he was concerned, the work for which he had been sent had been completed. All that remained was to follow his next instruction, which was to return to England in a manner he believed most appropriate.

Of the options available, Cook and his crew determined it best to set course westward until reaching the coast of New Holland, then turn north and head for the East Indies. Cook plotted a course for Van Dieman's Land, a section of the coast of Tasmania which Dutch navigator Abel Tasman had followed, mapped and claimed for the Netherlands in November 1642. On Sunday, 1 April 1770 Cook left New Zealand. Had he reached Van Dieman's Land, he may have discovered the strait (Bass Strait) separating that island from the mainland. However, nearing the end of the westward crossing of the Tasman Sea a storm blew him too far north and the coastline of Tasmania was not sighted.

Point Hicks, Vic. A monument marking Cook's landfall can be seen on the right side of the photograph

On the 18th April 1770, Cook wrote what many believe to be his "famous last words", a well-argued journal entry about the existence of Terra Australias, the great south land: "I do not believe such a thing exists, unless in a high latitude". Within 24 hours he was to be proved wrong, unless, as some historians argue, the continent of Australia was found to be exactly where he believed it to be - in a high latitude. While he knew from Dutch maps of Australia's existence, he may have subscribed to the commonly held belief that what the Dutch had sighted was just a string of islands and not a major land mass that stretched all the way south to Antarctica, which was Dalrymple's concept of what the great south land should be.

The first sighting of the Australian mainland occurred on the 19th April 1770 west of the southeastern prominence of the continent. Endeavour's log records the naming of Point Hicks "because Lieutenant Hicks was the first who discovered this Land". Whether Cook or Hicks actually first sighted land at Point Hicks is also a matter of considerable controversy as the bearings he gave for the land is in the middle of the ocean. For years the issue has been debated - some believe that what Hicks sighted was a cloud mass off the coast, others mention alternative landmarks and Brigadier L. Fitzgerald considers that what Hicks sighted was, in fact, Mount Raymond, a reasonably prominent peak situated about 10 miles East of Orbost. Suffice it to say, official sources have chosen to recognise what we now refer to as Point Hicks as Cook's first Australian landfall though it probably wasn't.

Peter Hibbs, an Abel Seaman of the First Fleet flagship HMS Sirius. was one of the few non-convict First Fleeters known to have settled in the Sydney region. Hibbs himself claimed, and there is some evidence, albeit circumstantial, to support his claim, that he had visited Botany Bay in 1770 as a cabin boy aboard James Cook's Endeavour. If that is so, he would be the only member of Cook's expedition to have returned to Australia with the First Fleet. Hibbs would have been 11 years old when the Endeavour sailed for Australia's shores. It was not uncommon for youths of that age to be taken to sea as cabin boys, but since they were under-age, their names were never recorded.

One compelling piece of circumstantial evidence that Hibbs was on board, and Cook had named his first first Australian landfall named after him, is an entry in Cook's journal on 11th October 1769: "(we saw) at Noon the SW Point of Poverty Bay which I have named Young Hicks Head after the Boy who first saw this land". The only person on board named Hicks was First Lieutenant Zachary Hicks, a senior officer of a similar age to his own and someone Cook would never refer to as "Young Hicks" or "the Boy". Elsewhere in the journal he makes many references to Hicks as Lieutenant Hicks. On the occasion of the first landfall, could Cook have been referring to a young boy named Hibbs whose name was misspelt when the journal was transcribed for publication

Cook's landing place, Botany Bay, Kurnell, NSW

Sailing north, Cook was hampered by disagreeable winds, and finally made for a shallow harbor at 34 degrees South latitude. He entered the bay on April 29th. and found native peoples (Tupaia could understand nothing in their language), plenty of firewood, good water, swampy and sandy shores, and many sting rays in the water. He at first called it Sting Ray Bay, but following the enthusiasm of Banks and Solander who brought aboard a variety of unique vegetation specimens, he changed its name to Botany Bay.

Though they were very good at collecting and identifying plants, Banks and Solander were less effective in identifying good farming land. The Quaternary alluvium (sand) around Botany Bay supported nice green swamps where poverty-stricken plants struggled for an existence, but the gentlemen botanists saw none of this, not when there was so much green around them. They gathered specimens, and Banks schemed to have this demi-Eden turned into a British settlement. It mattered little to him that the plants were growing on some of the worst soils to be found on this planet - to him, a botanist, it was a paradise of plants. On Banks' suggestion Botany Bay would become a destination for convict-laden boats arriving from England in 1788, a destination that had to be abandoned within days because of its unsuitability.

On the southern headland at the bay's entrance is the grave of Scottish Seamen Forbus (Forby) Sutherland, an Abel seaman of HMB Endeavour who died of tuberculosis on 30th April 1770, the day after the vessel was brought to anchor in Botany Bay. His body was brought ashore and buried the following day near a watering place used by the visitors (the small creek still flows today). Cook named the nearby headland Point Sutherland in his memory. A cairns marks the location.

Getting supplies was not as easy as was first assumed by Cook and his crew, from their initial observations of the native inhabitants. Whenever they tried to come ashore, they were confronted by members of the local clan. Little groups of blacks would appear from through the trees and stand for a moment to shout and throw a spear or two. Then they would vanish again into the bush. ... "All they seemed to want," Cook wrote, "was for us to be gone." His journal entry for Sunday, 6 May 1770 reads, "Having seen every thing this place afforded we at day light in the Morning weigh'd with a light breeze at NW and put to sea and the wind soon after coming to the Southward we steer'd along the shore NNE and at Noon we were by observation in the Latitude of 33 degrees 50 minutes South about 2 or 3 miles from the land and abreast of a Bay or Harbour wherein there apper'd to be safe anchorage which I call'd Port Jackson."

"During my stay in this harbour I caused the English colours to be displayed on shore every day, and the ship's name, and the date of the year to be inscribed upon one of the trees near the watering place." T.A. Gilfillin's painting titled 'Captain Cook taking possession of the Australian continent on behalf of the British Crown' was presented to the Philosophical Society of Victoria in 1889. Banks' greyhound is watching two men skin a kangaroo near the tent on the left of the painting. National Library of Australia.

Cook continued northward, naming features, always searching for good harbours and maintenance materials for his ship and crew. Cook came ashore at Bustard Bay and climbed Round Hill Head on Wednesday 24th May 1770, accompanied by the Botanist Joseph Banks and Dr Solander and a party of men to examine the local countryside. The Endeavour was anchored about 3 km off shore. This was Cook's second landing in Australia and his first in Queensland, hence the Town of 1770, located here, is referred to as the birthplace of Queensland.

The further north he travelled, the more difficult navigation became. Cook was being funnelled into the narrowing channel between the mainland and the maze of reefs of the Great Barrier Reef system. He continued sounding and naming features he observed before the Endeavor grounded on a reef on 10 June. Cannon, gear and ballast were jettisoned and after 23 hours, the Endeavour was floated free. A piece of coral was wedged into a hole in the hull of the vessel and a piece of heavy sail sewed with oakum yarn and dung by Midshipman Jonathon Monkhouse was strapped under the Endeavour's hull to minimise the entry of water. She was eventually brought to safety at the mouth of a river which Cook named after her. The Endeavour was beached and during a seven week sojourn, the hull was repaired. When the Endeavour finally set sail, it escaped away from the mainland and into the sea beyond the Reef.

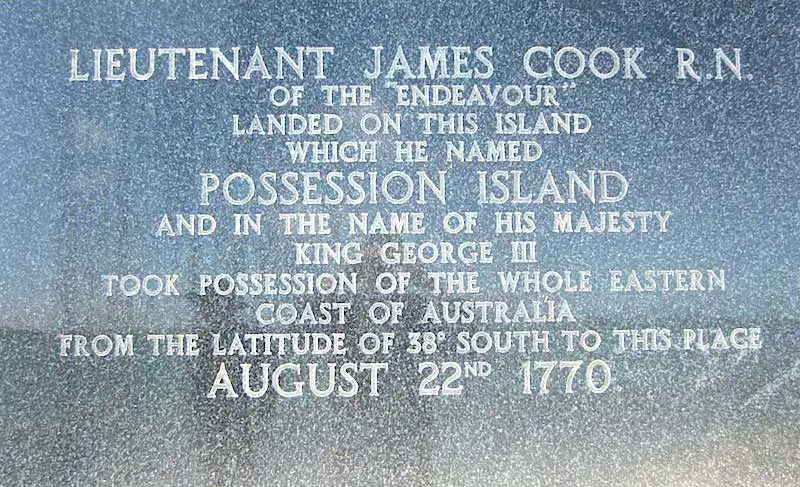

Cairn marking the spot where Cook claimed formal possession of New South Wales, Possession Island, Qld

On Tuesday, 21st August 1770, Cook reached the peninsula tip which he named York Cape in honour of His late Royal Highness the Duke of York. The next day he went ashore of an island in the York group (Possession Island) and proclaimed the lands he had discovered for the King. A monument marks the spot.

Cook gave the lands he had charted a new name; New Wales (he later amended it to New South Wales). When he claimed New South Wales for the British Crown on 22nd August 1770, his claim covered all the lands he had explored. The point of possession was the most easterly point he had visited, it was also and that point was located 142 degrees west of Greenwich, which placed it right on the line of demarkation between Portuguese and Spanish territory as determined by the Treaty of Saragossa or Treaty of Zaragoza, signed on 22nd April 1529. By claiming only territory he had visited, Cook was in fact claiming territory up to that line and no further, which amounted to the whole of that part of Australia which fell in Spain's half of the world. It is presumed that, to Cook, Dutch territory in New Holland would have extended east to that line of demarkation since the Dutch were aligned with the Portuguese. Britain had no quarms about walking in and taking over territory in Spain's half of the world, as evidenced by the Nootka Sound Incident of 1790 which brought the matter of international territory ownership to a head and resulted in the rules being changed forever, but Britain had no argument with the Portuguese or Dutch and respected their territorial rights and claims.

It was with great relief that Cook passed out of the reef and into Torres Strait. He realised that the waters he was now entering had been well plotted by years of Dutch and Portuguese presence, and therefore ceased charting the voyage. His route was to the coast of New Guinea, then west along the southern coast of Java and around the west end of the island into Batavia. Three months were spent in Batavia, which was rife with disease and general unhealthiness, conditions there no doubt contributed to the increased loss of life on the voyage home. Nicholas Young was first to sight Land's End and three days later the Anchor was dropped in the Downs, 13th July 1771. Cook's first voyage into the Pacific was over.

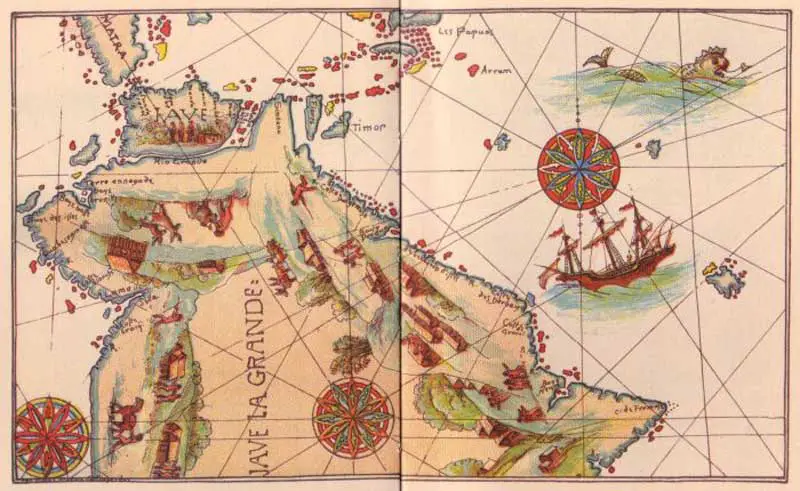

1787 map of the South Pacific and eastern section of Australia, the first to show their coastlines after having been mapped and named by Cook.

The accomplishment of Lieutenant James Cook in the Pacific regions during 1769 and 1770 are not easily distinguished without a solid understanding of methodology and accomplishment to that time and under the same conditions. Cook reported not as a traveller, but as a scientist, a scientist of geography. His journals are filled with the statement of winds and seas, tides and sunken rocks, the character of the lands, the habits of men. Cook gave quality to his discoveries unlike any before him or any imagined by the British Admiralty. He had taken a bay, a landfall, a vague strip of coast and presented to geography an outline, clear and defined, set and proportioned in the general scheme of knowledge. His technical competence under extreme conditions throughout the passage is superbly represented by his work off Cape Maria van Dieman and throughout the Great Barrier Reef labyrinth.

With only dead reckoning and his celestial abilities, Cook charted an unknown world with himself as his greatest asset. The historian Beaglehole said of Cook's accomplishments, "He had not discovered the great southern continent, but he had more than any other man made doubtful the thesis of its existence. He had not discovered Tahiti, but he gave that island of Venus and of George III a complete and rounded existence. He had not discovered New Zealand, but he had brilliantly reduced it to the dimensions of fact. He had not discovered New Holland, but he crystallised what was to become known as New South Wales; and he had shown that this eastern coast at least was no archipelago, but continuous land. He was the second and not the first captain to sail between Australia and New Guinea; but the act had both the force and the effect of a new discovery".

Alexander Dalrymple and the Royal Society of Britain had been a major influence in persuading the British Government to make a world observation of the transit of Venus across the path of the sun in June 1769, and offered the society's funds to help finance a British expedition into the South Pacific for this purpose. For both Dalrymple and the Government, the trip always had a double adjenda; Darymple saw it as a chance to prove once and for all that the south land, or Terra Australia, existed; the British Government saw it as an opportunity to grab some territory from the Spaniards and further consolidate its Empire, although this was probably not known to Dalrymple at the time. The American War of Independence, which saw the American colonies break free from British rule, was still 7 years away, but the signs of discontent were clear and the British were already looking elsewhere for new territory.

The dumping of Dalrymple as the leader of the expedition for a naval man was hard enough for him to take, but when he discovered that the navy's choice, Lieut. James Cook, not only did not share his belief in the existence of a south land but had embarked on the voyage with the intent of disproving its existence rather than proving it, Dalrymple was far from impressed. From that time on, he was bitter towards Cook and took every opportunity he could to discredit him and his achievements, partularly those of his first Pacific voyage.

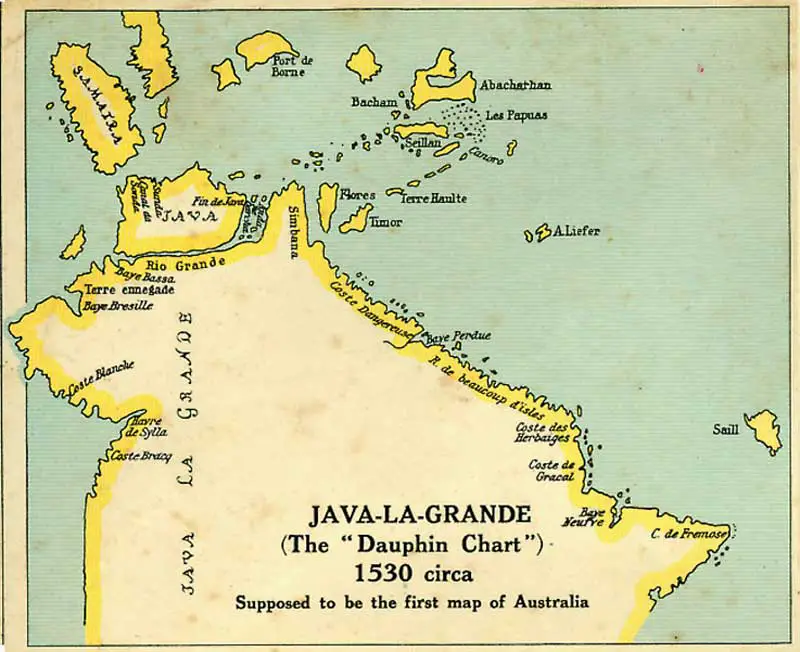

In Matthew Flinders' "A Voyage to Terra Australia", the great explorer recorded that he knew of the existence of a French chart which marked "extensive country south of Moluccas under the name Great Java; which agrees nearer with the position and extent of Terra Australia than with any other land; and the direction given to some parts of the coast, approaches too near the truth, for the whole to have been marked from conjecture alone."

The map Flinders was referring to was probably the one given to Henry VIII, or a similar one in the posession of the British Admiralty's hydrographer, Alexander Dalrymple, to assist him during his planned voyage of discovery in the Pacific which Lieut. James Cook eventually made in his place. Dalrymple never admitted to offering or giving a copy of the map to Cook, or for that matter withholding it from him either, but in 1786, he startled the world by announcing in a postscript to a pamphlet on the Chagos Islands that despite Cook's supposedly triumphant first discovery of the eastern coast of Australia, that honour really belonged to the Portuguese.

As evidence, he cited the Dauphin map. One of the coastal features marked on the east coast of Java Le Grande is called Coste des Herbiages. Its location is on the same stretch of coastline where, in April 1770, Cook came ashore, and stayed for a week to allow Sir Joseph Banks and Dr Solander to collect botanical specimens. Cook originally called the bay Sting-Ray Harbour but changed it to Botany Bay, which, translated in French, is Baye des Herbiages. By citing the map, Dalrymple had by implication accused Cook of fraudulently accepting recognition for the discovery, which may explain Cook's undue modesty in not viewing his work about Australia as being great. A strings of islands and/or reefs line the coast of the equivalent of North Queensland exactly where the Great Barrier Reef is.

With eleven known versions of the map having been produced and circulated throughout Europe, two of which had been produced by a cartographer who was in the employ of the palace of the King of England and both were in the King's posession, it is hard to believe that the British Admiralty, being one of the most powerful naval forces in the world at that time didn't have a copy, or make an attempt to obtain one, knowing how much assiatance it would have given Cook who was about to embark on a voyage to the very places marked on these maps. Another copy of the map had been in the possession of Edward Hartley, Earl of Oxford, until his death in 1724, though it does not re-appear in documentation until 1786 when Dr Solander is said to have found it. Sir Joseph Banks, who sailed with Cook and Solander to Botany Bay, is known to have been given a copy of the map by Dalrymple, but it is not known if this was before or after the voyage to Botany Bay.

That all begs the question, does Cook's journal give any hints as to whether or not he had the Dieppe map by his side as he navigated the waters of the east coast of Australia? The school of thought which subscribes to the argument that Cook's voyage was one of re-discovery rather than discovery believes it does. After the Endeavour was holed on the Great Barrier Reef, Cook gave orders to sail on through unfamilar waters to the NW of where he went straight to the only safe harbour within 1,000 km near present day Cooktown. A navigator of Cook's calibre and experience would always head for the nearest coast, rather than unfamiliar, uncharted waters ahead if his ship was holed and struggling to stay afloat. Cooktown harbour is clearly shown on the Dauphin map as the only harbour on this stretch of coastline which is appropriately marked as Coste Dangereuse. The Great Barrier Reef is also marked as an extended shoal.

Upon entering the harbour, Cook noted in his journal that he "found [the channel] very narrow, and the harbour much smaller than I had been told". Told by whom? A Botany Bay aboriginal? a lookout on his ship? Perhaps the map itself holds the answer. The Dieppe map in the posession of the Earl of Oxford was drawn by the French cartographer, Nicolas Desliens. His are generally accepted as the most accurately detailed of the Dieppe maps. Desliens' maps show Cooktown Harbour as large, well sheltered and landlocked, whereas Cook found it to be round and more open. Of interest is that the publisher of Cook's journal, Dr J. Hawkesworth, had changed the origin text in Cook's handwriting to read, "smaller than I had expected" on publication.

Adding to the puzzle is the unlikelihood of Cook expressing his confidence that this coast 'was never seen or visited by Europeans before us' if he in fact had been following a chart made by a previous European visitor. Such a statement would amount to blatant deception. Did he then say that, or were these words added by the publisher? Cook had a reputation as a very honest man and on other occasions where there was an element of doubt about a matter, he always acknowledged this doubt and never claimed credit for anything which was proved later to be incorrect.

Did Mendonca and Cook give Botany Bay the same name by co-incidence? Would Cook have risked his repution by "borrowing" the name, knowing that one day he would be caught out and his reputation tarnished? Did Cook ever actually claim to discover the east coast of Australia (his journal indicates he did, however the publisher of his journals made a number of changes to what Cook wrote, at times altering the meaning and implication), or is it something the world thrust upon him and he was too embarrassed to disagree with them? Like the question of which European was the first to enter the Sydney region, the answer may never be known.

In his pamphlet on the Chagos Islands, Dalrymple indicated that another, more sinister cover-up by the British Government had taken place and implicated Cook as part of the plot. He, and a string of historians after him, pointed out that there was perhaps more to Cook's claim of a large slab of the Australian continent than first meets the eye. Dalrymple observed that, by defeating Spain in the Seven Year War in 1760, the British Government eroneously believed it had a right to take over any territory within Spain's domain that it desired, and that Cook's Pacific voyages were launched for no other reason than to extend the British Empire. Without saying it in as many words, he was accusing the British Government of using the Royal Society's funds to finance its Empire building activities by getting the society to share the cost of Cook's first Pacific voyage.

He pointed out that by fixing the western extremity of New South Wales as British territory at Longitude 142 degrees east of Greenwich and claiming it for England (the British Government was later to take an extra 5 degrees of longitude without telling anyone), Cook had only claimed claimed what he did and no more because it territory on the Spanish side of the north-south line of demarkation as set by the the Treaty of Saragossa in 1529. Dalrymple argued that Cook could have and should have continued exploring further but didn't, and the only reason he stopped was because he was told to, and the only reason he was told to was bcause his mission - to claim territory from Spain - had been accomplished.

Cook did not claim the land for England at his first landfall, or even at Botany Bay, where he stayed longest and which his expedition members identified as the most likely location of all he had seen as a site for a future colony. Rather, he waited until the last day of his exploration, selecting the most westerly point of his voyage up the east coast of Australia before heading home as the spot where he claimed the land for England. Did he wait until the last day so that his claim included as much territory as possible (all he had visited) or did it become the last day because, having now reached the Spanish/Portuguese line of demarkation, all that needed to be done to complete his task - claiming the Spanish part of Australia for England - was raise the British flag, claim the whole of where he had been for King George and then head for home, mission accomplished.

If Cook's territorial proclamation was part of his original commision, which seems likely, then Dalrymple was correct. The observation of the transit of Venus may well have been a convenient smokecreen to cover up the real reason for the British Government sending Cook and not Dalrymple to the South Pacific - to find the south land and take the possession of it away from Spain. The establishment of a British penal colony in this most unlikely location 18 years later, and the claims made under Governor Arthur Phillip's commission, serve only to reiterate this. The secret instructions given to Cook by his superiors bear witness to this, but they also exonerate Cook of any underhanded actions in the matter, as he did not create the secret orders, he simply carried them out.